Posted: March 27th, 2010 | Author: yangwu | Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: city image, urbanization | No Comments »

“The Beauty of YinZhou”, is it beautiful in your eye?!

“鄞州之美”,美ä¸ç¾Ž?!

Finally, human being move into the city…and finally humen being evolve to the “animals”?!!…

人类æ¥åˆ°äº†åŸŽå¸‚,进化æˆäº†”动物”?!!~~

(PS, the direct interpretaion of this ad. is: Weekend animals in the night light…are exceedingly fascinating and charming!)

2 functions presented by the wall: enclosure movement+propaganda=legitimacy

一墙两用:圈地è¿åŠ¨+å®£ä¼ å·¥å…·=拆è¿æœ‰é“,æ”¹é€ åˆç†

Rape flowers: Survived after” raped”, still blooming and lovely~~

æ²¹èœèŠ±(英文åRape flower!): “蹂躔之åŽä¾ç„¶åšå¼ºå¹¶ç»½æ”¾ç€~~

After demolition, before exploitation, it’s the “sweet” home of informal immigrants

拆è¿åŽ,å¼€å‘å‰çš„闲置地是农民工的临时房和èœåœ°.

有人说过:世界上最美的建ç‘是废墟. 更甚, 废墟还有ä¸æ»ä¹‹çµ~~

Someone said that: the most beautiful architecture is the ruins. More than that..this ruin never die~~

Rarely the case: one lucky ancient town “living” in city~

难得眼å‰ä¸€äº®…ä¿ç•™å®Œæ•´çš„城ä¸æ‘

The truth is: we need to “protect” our heritage…but how to define which is heritage and which not?

文化é—产所以留下…å› ä¸ºè¿˜æœ‰ä»·å€¼?

No reason…some part of my heart was touched in this moment!

没æ¥ç”±çš„~~心抽了一下下~

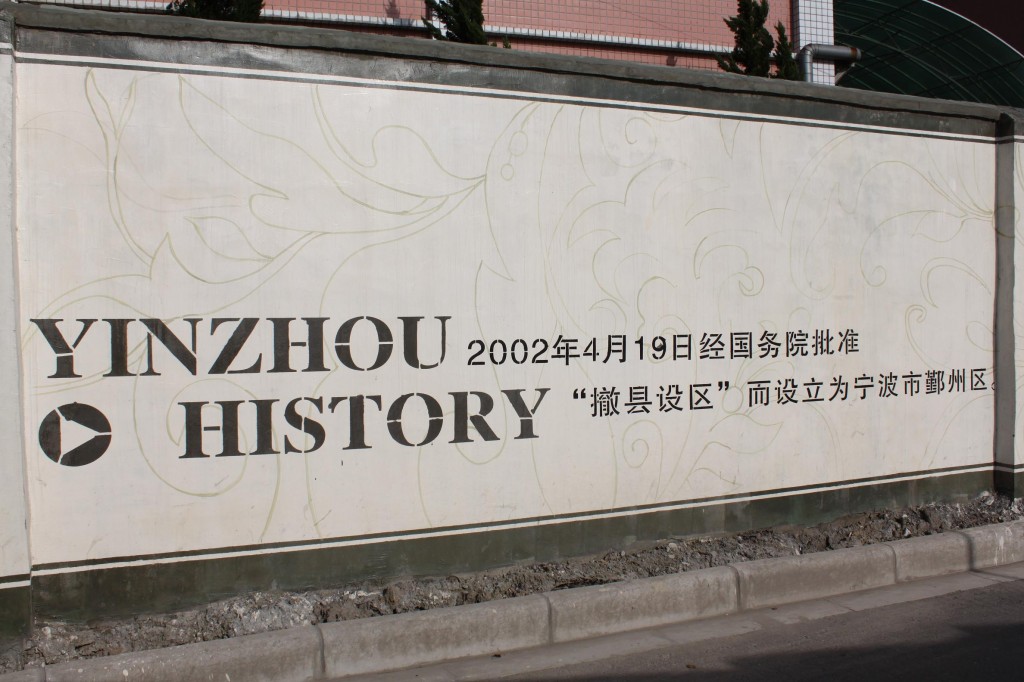

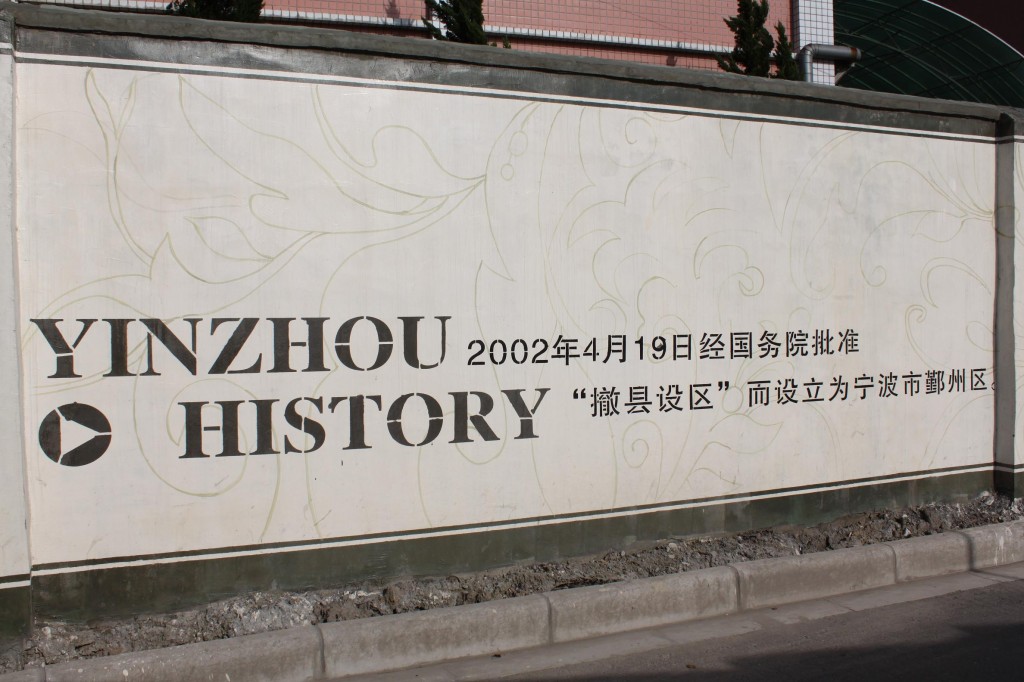

The historic point of Yinzhou urbanization: title changed from “county” to “district”?!

“撤县设区”的历å²èŠ‚点象å¾äº†ä»€ä¹ˆ:城市化?!

The “economic development zone” under bridge…thanks to the golden land of city

寸土寸金:大桥下的”ç»æµŽå¼€å‘区”

Now, should we count down for what?! Benz, ICBC, or sponsor’s ad expire date?

时间为è°è€Œæ¢æ¥~~奔驰? ICBC?赞助商们?!

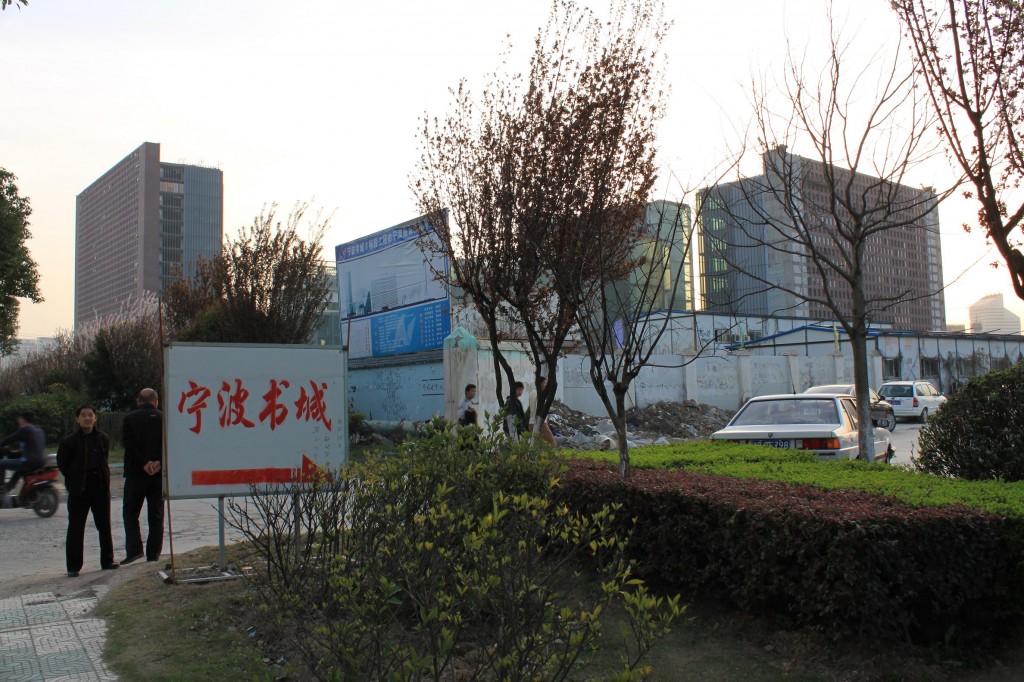

Book City

书城

Situated oppositely to Ningbo LaoWaiTan, formerly the place of old flour factory. One vivid comment on this change is very impressive, so allow me to quote here: this plant, before producing food for body, now upgrades to produce food for mind.

ä½äºŽå¤–滩对岸,原é¢ç²‰åŽ‚ä½ç½®. 有ç§è¯´æ³•ï¼Œå€¼å¾—一æ…以å‰ç”Ÿäº§ç²®é£Ÿ~~现在,æ供精神粮食

The spot next to Book City is another imaginary landmark of Ningbo: Fortune Centre.The question is, can it be a real name card of Ningbo? Or just another non-place?!

书城下一站,财富ä¸å¿ƒï¼Œå¦ä¸€ä¸ªæœªæ¥çš„å®æ³¢åœ°æ ‡ï¼Žä½†æ˜¯ï¼Œå…¶èƒ½å¦æˆä¸ºä¸€å¼ å副其实的城市å片呢?

外滩北岸第三站:和丰创æ„广场.

The third spot of this industrial chain is HeFeng Creative Square

What you can get from a bunch of wall advertisements: creative centre + business centre + city centre=potential stock in real estate?!

丰富的外墙广告:创æ„+商场+地段=地产ä¸çš„潜力股?!

(PS : English version of wall ads.

pic1: The creativity headquater of chinese designers

pic2: stylish resturants, creative retails, high-end leisure centre, and in-style industies…

pic3: JinYi 5 stars cinena and Four Season HeFeng hotel join in.

pic4: Location in the mouth of 3 rivers, scarce and rare lots…

The Slogan: Create World, Win Future

æ ‡è¯:创世界 赢未æ¥

Posted: March 26th, 2010 | Author: yangwu | Filed under: creative industries | Tags: creative clusters | No Comments »

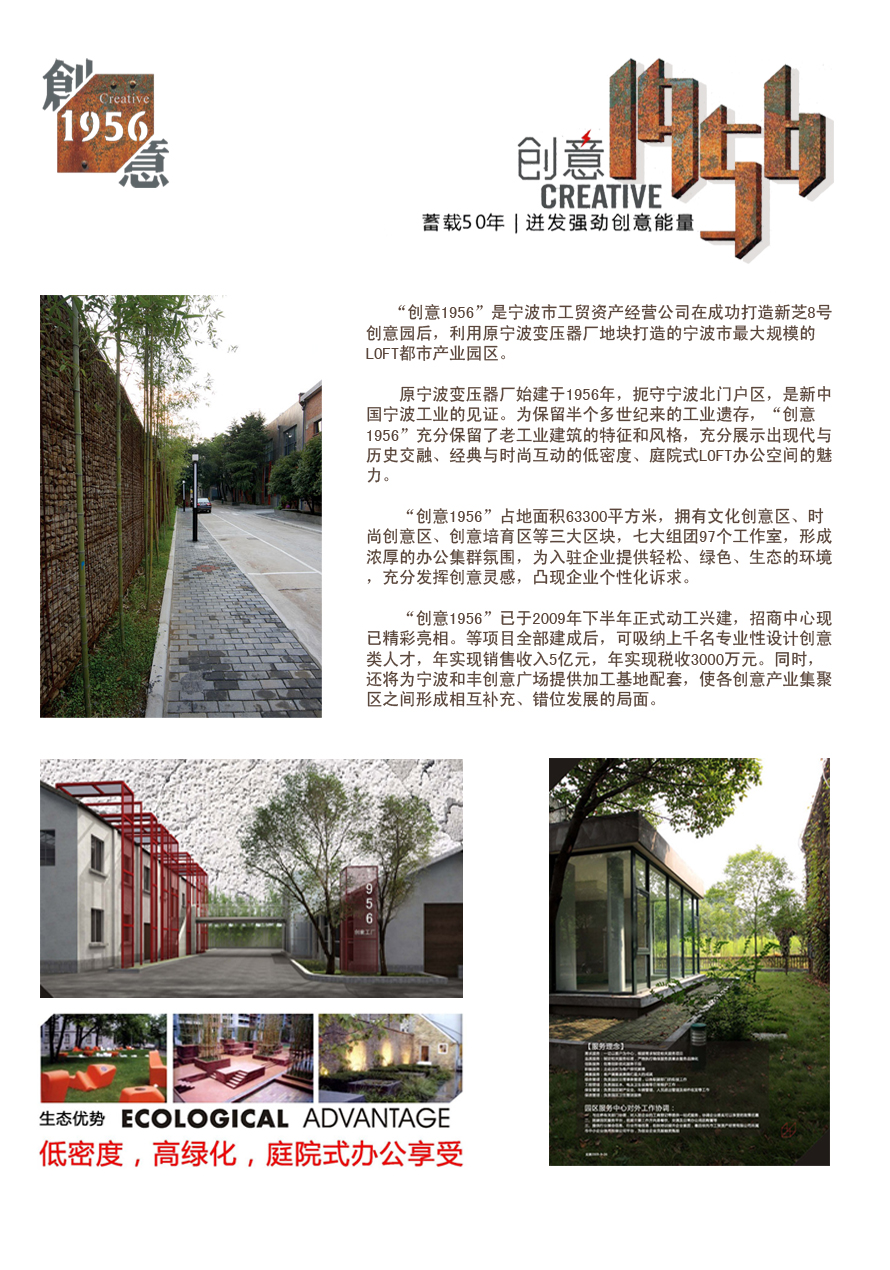

Got a first spot to visit: Creative1956… formerly one of the state-owned factory of transformer manufacturing, now is changing to an imaginary plant for producing creativity…It’s said that this is going to be the largest loft basement in Ningbo~~Should we go and see how is everything going there?!

打å¬åˆ°ä¸€ä¸ªåœ°:创æ„1956~~原å˜åŽ‹åŽ‚改建的~~å¬é—»,è¦æ•´è£…æˆå®æ³¢æœ€å¤§ä¸€LOFT基地…这就去拜访一下å§!

The Planning Map~

规划图~

A first sight, Poor Gate!!… The factory sign was abandoned and took off!~~However, lucky for it, in near future, a new exterior signage will have its new name framed here, reminding the original birthday of this place:1956

å±å’äº†å‡ å年的国è¥å˜åŽ‹åŽ‚!如今,门头也被拆了!ä¸è¿‡ï¼Œæ–°ç‰Œå·åˆ›æ„1956ä¿ç•™äº†å…¶æœ€åŽ†å²çš„部分~~OK啦~

Look from this way (oppositely): green lane …beautiful sight~~~

å¦ä¸€è¾¹çš„风景很好…绿æ„浓浓的林è«å¤§é“~~

Beside, several boilers still stand erect..Though, it’s of no use now, one might remember its busy days back to the new China’s industrial revolution period.

远处åšå¼ºå±¹ç«‹ç€çš„å‡ ä¸ªå¤§é”…ç‚‰ï¼Œä¾ç¨€èƒ½çœ‹å‡ºå½“å¹´æ–°ä¸å›½å·¥ä¸š”é©å‘½”时期”大干了一场”的风采啊

Basically, the building structure has no change~ Red colour steel bars are newly included elements, transforming the old manufacturing plant into another creative workshop!!

PS: Here located Loft group No.1 and No.2: centres for industrial design, architect design, IT and the relevant allocation.

基本上è€æˆ¿çš„原结构ä¿æŒä¸å˜…红色的钢ç‹é“éª¨æ˜¯åŠ å…¥çš„æ–°å…ƒç´ ~~~åˆ¶é€ å·¥åŽ‚ä¾¿æ‘‡èº«ä¸€å˜åˆ›æ„工场啦~PS:æ¤ä¸º1å·åŸºåœ°,主打工业设计,建ç‘设计, ITåŠç›¸å…³~

A small, cute garden got reserved~~In those days, most state-owned factories had such facilities (small area for leisure)…so… while mothers and dads were working in the workshop, their children can play  around or do homework ~~

PS: Loft group No.3 is here, proposing for planar and 3D design,film and image design, and the relevant allocation.

ä¿ç•™äº†å°èŠ±å›~那个年代的国è¥åŽ‚æˆ¿éƒ½è¿™æ ·…大人上ç,å°å©è¿˜æœ‰ä¸ªåœ°å¯ä»¥æ’’野~~

PS:3å·ç»„楼集åˆå¹³é¢ï¼Œ3D设计,电影和形象设计åŠå…¶ä»–相关é…ç½®

By reading after the planning map, it seems that this group of lofts hasn’t been appointed any specific business type…Will it be the place only for eating and drinking (reserved for consumption)?~~

仔细对照规划图, å‘现这组楼用途ä¸æ˜Ž,éš¾é“是åƒåƒå–å–区?~

Loft group No.5 for film industries…several independent Lofts, one sticking to another…Not sure how to use, but it could be a perfect place for film studio, right?!

5å·ç»„楼~~摄影行业。一个一个独立的框架LOFT…éš¾é“是摄影棚~~

This should a huge job of “replacing”~~almost rebuilding the workshop~~only the underground basis got saved!

这个翻的彻底了~~就差没撬地基了!

Simple and clean roof…functions well too~~

简å•æ¸…爽功能ä¸å¼±çš„屋顶~~

The “Uniform” of the outsider walls~

统一的外墙~~

An overall view~

整体效果一览~

The buildings are short…lane is not too narrow…which is good for eyesight and walking experience~

å°çŸ®æˆ¿åŠ 宽间跅视野很好ä¸åŽ‹è¿«~~

No.6-7 for decoration and university students field work base.

6-7å·åŸºåœ°ï¼šè£…饰类,大å¦ç”Ÿåˆ›æ„区

Loft No.7 was formerly a heat treatment workshop…really really huge…

7å·æ¥¼å‰èº«æ˜¯ä¸ªçƒå¤„ç†è½¦é—´,很大很大…

The roof should be new one…here is a zoom-in detail picture: the steel skeleton with bright red colour looks impressive and powerful…

顶应该是掀过了æ¢æ–°çš„~细节图~~红色的新骨架很亮眼很扎实亚~~

Should this old chimney be packaged into a creative vintage landmark?!

大烟囱会被包装æˆåˆ›æ„åœ°æ ‡å—?!

Posted: November 18th, 2009 | Author: admin | Filed under: waste industries | No Comments »

[By Ned Rossiter, published in International Review of Information Ethics 11 (2009)]

‘As long as there are people on this planet, the waste industries will never die. So we’re not worried about the future of the industry’.

– Owner of a small e-waste processing business in Ningbo, China.

This essay is interested in the relationship between electronic waste and emergent regimes of labour control operative within the global logistics industry, the task of which is to manage the movement of people and things in the interests of communication, transport and economic efficiencies. Central to logistics is the question and scope of governance – both of labouring subjects and the treatment of objects or things. The relation between labour and electronic waste constitutes a milieu (environment) and population (of human and technological life) whose communication comprises a unique multi-scalar space that severely tests techno-systems of governance. In registering the contingency of governance – its capacity for failure or oversight – this essay signals the uncertainty that underpins the technics of control special to logistics. At stake is the connection between the milieu and the labour of human life.

Paradoxically perhaps, conflicting governance regimes make possible the production of non-governable subjects and spaces. Electronic waste and many of those working in its informal secondary economies can be considered as occupants that reside off the grid. Such positioning in itself does not constitute a political program or articulated agency. Non-governance should not, in other words, be assumed to be synonymous with some kind of counter-political force. This would be the error of translation understood as a system of equivalence in which an a priori relation exists between, for instance, non-state actors and political agency. Indeed, it may even be desirable for biopolitical powers to ensure a non-governable dimension in order to manage the political, economic and environmental problem of electronic waste – the maintenance of unregulated informality serves as one of the structural resources that sustains the current economy of waste. Since there is no globally implemented consensus or treaty and quite frequently an absence of national legislation on how to address the economic and social life of electronic waste, it helps to reflect on the question of e-waste by taking this ‘indifferent’ status of e-waste as a point of departure – both technically within logistics software and politically within the institutional limits of the state apparatus. As I argue below, such indifference comes at a potential political and social cost, one that sees a further expansion and penetration of biopolitical technologies of control over the relatively autonomous aspects of labour and life.

To complement the various hypotheses above, this essay also addresses the relation between regions and the composition of labour in electronic waste industries in China. The multiplication of regions through practices of translation coextensive with the movement of people, language, technological protocols and things presents a serious challenge to regions as they are defined by hegemonic orders and interests. A region such as the European Union, for example, is translated as a legitimate political, economic and social entity through an ensemble of institutions (state governments, international institutions, universities, cultural organizations, labour unions, etc.). While there may be numerous instances of dispute and conflict between such actors, ultimately the fact of their relation serves to mutually reaffirm the legitimacy of the EU as a region. But to reduce the configuration of a region to such translation devices alone is to overlook the diverse practices and technics through which spaces and populations are comprised. The battle of hegemony, in this sense, is a contest over idioms of translation.

Similarly, the social practice of translation brings into question the analytical modalities that assume the existence of the region as a set of stable coordinates and coherent institutional practices that facilitate economies of depletion. In the case of the global logistics industries, the rise of secondary resource flows accompanying the economy of electronic waste is coextensive with the production of non-governable subjects and spaces. I suggest that the relation between these entities constitutes new regional formations that hold a range of implications for biopolitical technologies of control.

Multiplication and Division

With their capacity to adapt flexibly to a range of circumstances and skill requirements, the rural migrant worker in China is arguably the exemplary post-Fordist subject rather than, as often assumed, the specialist work of the designer, architect, filmmaker or ad-man attributed to the figure of cognitive, creative or immaterial labour. Such a distinction in the body of labour-power points also to the residual class dimension of post-Fordist labour, which in this case is frequently underscored by the spatial division between rural provinces and metropolitan centres. Ethnic divisions also prevail, with the rural migrant worker often enough not belonging to the Han Chinese majority population.

Fieldwork undertaken earlier this year with my MA students in Ningbo – a 2nd tier and major port city a few hours south of Shanghai – began to make visible (at least for us) the ‘division and multiplication of labour’ within the electronic waste industries. Mezzadra and Neilson:

By speaking of the multiplication of labor we want to point to the fact that division works in a fundamentally different way than it does in the world as constructed within the frame of the international division of labor. It tends itself to function through a continuous multiplication of control devices that correspond to the multiplication of labor regimes and the subjectivities implied by them within each single space constructed as separate within models of the international division of labor. Corollary to this is the presence of particular kinds of labor regimes across different global and local spaces. This leads to a situation where the division of labor must be considered within a multiplicity of overlapping sites that are themselves internally heterogeneous.

And as Neilson elaborates elsewhere:

It is crucial to note that the multiplication of labour does not exclude its division …. Indeed, multiplication implies division, or, even more strongly, we can say multiplication is a form of division.

Hierarchies of labour separate the first stage of waste processing and storage from the initial collection of unwanted trash in the cities of China. The looped tape recording of diannao (computer/electronic brain) and kongtiao (air conditioner) rhythmically alerts locals to the arrival of the junk men and women as they move about neighbourhoods on a bicycle equipped with a flat tray for the transport of waste. Situated among those at the bottom of the supply chain of electronic waste industries (others working in particularly toxic conditions include children who dissemble electronic products, stripping copper from plastic casings while inhaling poisonous fumes from incineration), the junkmen are among the most transient in the economy of e-waste. The working life of junkmen is one of low income and frequently changing low-skill jobs determined by the fluctuation of market economies and the informal social networks and family demands that shape the movement of populations from country to city, job to job. Here, we see the multiplying effect of labour: while hierarchically distinct from other modalities of work in the economic life of electronic waste, the job of the junk men and women is underscored by mobility and uncertain transformation. It is unlikely, in other words, that waste collection is a job for life.

A different story prevails, however, in the case of many of the small businesses that deal with the sorting of electronic waste. Like many Chinese cities, the waste collection centres dispersed across the neighborhoods and districts of Ningbo are pivotal sites in the social and economic life of electronic waste. Often run as small family businesses, these recycling centres can be divided along formal and informal lines, both with differing degrees of toxicity in terms of the type of waste materials collected. Of the thousand or so businesses with official licenses to operate in Ningbo (a legal requirement in Zhejiang province), there are many more that exist illegally. At 6000 RMB (approx. 600 Euros), the annual license fee is a costly obstacle for many, yet it offers a level of economic and political security not afforded by the illegal collection centres. The official sites tend to have a regular network of waste suppliers based on guanxi (social relations or networks) and, unlike the illegal sites, do not negotiate prices. This in turn affords the junkmen a level of guaranteed income, albeit with wildly fluctuating and typically declining prices over the past year. Trading prices for metals are set each morning according to futures markets, which are usually accessed as daily updates by mobile phone more often than through computers.

External and internal forces have placed enormous pressure on the recycling industry and labour conditions across China. The owner of one small licensed recycling company we spoke to, who had been in business for 15 years, made note of the Chinese Labor Contract Law, which came into effect in January 2008, making it harder for companies to sack employees. He offered this reference as an indication of the more stable and secure working conditions for the migrants he employs from Jiangxi and Húnán provinces to the west of coastal Zhejiang.

By contrast, reports produced by various human rights NGOs and environmental monitoring organizations document numerous instances where workers’ rights are violated in the electronics factories and recycling industries, with excessive and often unpaid working hours, hiring of child labour, gender divisions, dangerous working conditions, suppression of efforts to organize labour and strike actions, fines and punishments for violation of highly punitive rules (correct haircuts, smoking in designated areas, improper attire, wastage of water, making noise, posting or distributing unauthorized articles, etc.). More broadly, in her assessment of the legislative reform of labour conditions, Jenny Chan notes ‘severe rights violations in at least three major areas: job security; the use of contingent labor; and fair, fixed-term labor contracts’. Worker layoffs from factories have also been on the rise since the end of the Chinese new year – the social effects of this became rapidly clear, if relatively short-lived, on the streets of Shanghai and Ningbo, with increased numbers of homeless migrants and visible instances of untreated mental illnesses.

Improved labour conditions are often perceived by businesses and investors to come at a cost rather than a benefit in terms of higher productivity through workplace stability. Other economic forces impact in more immediate ways. Since 1st of January 2009, recycling companies have had to absorb the cost of a 17% value added tax – a burden not suffered by other industries. This comes on top of an enormous drop in prices of around 50-60% for recyclable metals due to the global economic recession. With successive months of depressed prices, the global recycling economy is now dire. In China, this manifests in the form of massive stockpiling of waste that cannot be sold. There are additional storage costs and increased health risks associated with prolonged exposure to inventory accumulation of toxic metals, to say nothing of increased pressures on labour.

Another owner of a Ningbo recycling business, Mr Yu, assessed the situation in the following way earlier this year:

Metals and papers are online transactions. Copper and aluminum are sold and bought in the futures markets. For China, marketing Chinese products is fine, however, in the global market it is hard to do good business. I have to purchase and sell the waste at cheap prices. I suppose the economy will improve. Copper makes more profits, however it makes me lose more money. Now the price of copper is 17 yuan/500 grams compared with the previous price (27/28 yuan / 500g) – we lose 10 yuan per 500g. We are a small business. Foreign waste such as plastic, copper and aluminum are packaged and put into containers that are transported to Beilun dock.

The Battle of Standards

The connection made here between electronic waste and the maritime industries is worth noting. Despite the fact that importation of electronic waste in China has been illegal since 1996, much of the movement of waste from North America, Europe, East Asia and Australia is channeled through the ports of China. There’s a story to be told here about the global logistics industry. In short, logistics is concerned with the management of global supply chains and labour regimes. The electronic waste industries obviously fit into that schematic. Aided by software applications and database technologies, logistics aims to maximize efficiencies at all levels. In terms of labour management, the optimum state of governance arises at the moment in which the execution of a task, or Standard Operating Procedure (SOP), is registered in the real-time computation of Key Performance Indicators (or KPIs). In other words, the labour control regime is programmed into the logistics chain at the level of code. Similarly, the governance of labour is informatized in such a way that the border between undertaking a task and reporting its completion has become closed or indistinct. As such, there is no longer a temporal delay between the execution of duties and their statistical measure.

The potential for escape, invention and refusal become severely compromised within such a biopolitical regime of control, one that is already dominant for millions working across the world in different industries articulated with global logistics systems. Moreover, and most oddly, it would seem that the capacity for capital to renew itself is substantially challenged within such a system: logistics aims to diminish the force of contingency, which plays a key role in the emergence of innovation upon which the reproduction of capital depends. Do we find here, then, an instance whereby capital programs its own obsolescence?

An important control device in the maritime industries is radio-frequency identification (RFID) technology, which registers the geographic position of ships and goods and assists in the management of inventories and the efficiency of supply chains. While RFID technologies are indifferent to the matter of things, and thus do not discern between, say, automotive parts or textiles on the one hand, and electronic waste on the other, their database logic nonetheless identifies the content of motion. In other words, the database provides a record of that which migrates from one place to another. And in the case of electronic waste, there are strict national and international regulations governing its transport and treatment. But since, as noted earlier, electronic waste is deemed an illegal import in China, it is questionable whether it falls into the purview of the database and its informatized sovereign power. Like many countries, electronic waste holds a contradictory status within the rule of law in China, with waste businesses requiring a license to operate, as mentioned previously.

In another respect, the connection between electronic waste, logistics and software systems constitutes the battle of standards across idioms of translation. The governance of labour associated with electronic waste varies enormously depending upon whether or not the movement, economy and treatment of e-waste is made visible by logistics software used in maritime logistics, to take one example. In such a case, there are industry, state and union standards that shape the conditions of labour and management of waste. Logistics software facilitates such relations by tracking cargo movement, registering times of passage in global supply chains and accounting for inventory accumulation. The standards established in such an economy run into conflict, or are just modulated differently, when the circuits of labour and resource flows associated with electronic waste are translated through less formal standards found in economies not officiated by the state. The case of electronic waste in China is one of these economies. The sex-trade in and across many countries and regions would be another.

Translation can be understood in one sense as the process of establishing standards expressed through a community of practice. In Naoki Sakai’s terms, this is the ‘homolingual’ operation of translation. Yet such an occasion should not be seen as the end-point of translation, but rather in terms of the instantiation of a particular border that promulgates new modes of practice and relation. Indeed, it is precisely the scene of conflict that attends the drive toward standardization that raises the problem of translation. The example of standardization in the shipping and transport industries helps clarify this process.

The standardization of shipping containers from the 1950s was accompanied by disputes between engineers, corporations and governments over competing economic and geopolitical interests in the transport industries. By the 1970s a global standard in containerization had been established, around the same time economic globalization came into full swing following the end of the Bretton Woods Accord in 1971 and the oil crisis of 1973. Such cursory contextualization indicates that standard containers did not alone determine or create economic accumulation (the same might be said for logistics software). Marc Levinson notes that by the late 1960s,

The economic benefit of standardization … was still not clear. Containers of 10, 20, 30 and 40 feet had become American and international standards, but the neat arithmetic relationship among the ‘standard’ sizes did not translate into demand by shippers or ship lines. Not a single ship was using 30-foot containers. Only a handful of 10-foot containers had been purchased, and the main carrier using them soon concluded that it would not buy any more. As for 20-foot containers, land carriers hated them.

Conflicts over standards in logistics and software systems define the terrain of translation in more recent years. Logistics, as defined earlier, is concerned with maximizing efficiencies in global supply chains and labour regimes. Once the logistical problem of container standardization had been resolved, the work and political economy of translation shifted to data standards. While present in a primitive form in the 1960s, the computerization of transport industries did not really take off until the 1980s following the standardization of shipping containers and the advent of just-in-time production. Effectively integrating and simulating the logic of containerization in order to produce enhanced efficiencies, the information architecture of code can also be understood as a container or silo formation. Again, the drive toward interoperability across different software systems is an example of translation as homolingual address or equivalence. Software technologies are key devices in the translation of labour and the mobility of things as actionable, visible and subject to control and instrumental consolidation. Once registered within the database logic of informatized sovereignty, electronic waste and its modalities of labour and social life become governable within the economy of real-time. Such an idiom of translation is one of co-figuration and equivalence, to draw on the formulation of Sakai. Yet logistics software consists of multiple standards whose disparities in code produce conflict and competition in the effort to determine systems commensurate with the demand for intermodal freight transportation, pervasive labour management and economic hegemony. Such tensions over standardization give rise to the heterolingual dimension of translation – its social practices of ‘differential inclusion’, struggle and multiplication – that confers a non-governable potential to electronic waste.

While I am in no way idealizing such practices – as noted earlier, there is enormous social, environmental and individual damage that attends the toxic life of electronic waste – I wish to stress that once captured within the instrumental world of logistics that economizes labour, life and space according to efficiencies in time, the work of translation becomes automated and effectively annulled. And it is precisely at this moment of informatization coupled with logistics that the region becomes constituted within the sovereign space of the database. Once code is king the variable capacity of labour, life and things finds itself subject to an intensive form of territorial and proprietary control that formal settings such as ASEAN, APEC and NAFTA can only gesture towards. But no matter how much communication regimes may be indifferent to noise, contingency, feedback and indeed life itself, the difference necessary for the work of translation is never entirely eradicated by techno-scientific systems. More likely certain modes of labour and life simply migrate off the radar and subsist instead in a world of non-governance, by which I mean idioms of expression, practice and economy external to the state-corporate nexus that defines contemporary sovereign power.

The Limits of Translation

With its indifference to matter, substance or qualities and concern instead with the management of mobilities and efficiencies of action, logistics dispenses with borders that distinguish labour, life and milieu. In doing so, the constitutive differences that make possible the translation of relations between labour, discourses, social-technical practices, economies and geocultural formations is surrendered to the world of ubiquitous homologies. What I am calling ‘ubiquitous homologies’ stems from the political economy of globalizing design industries (where architecture begins to resemble a sports shoe, toothbrush, motorbike, office chair, computer monitor, etc.), and shares something with what Sakai terms ‘co-figuration’, ‘linguistic equivalence’ and ‘homolingual address’ – all of which are homogenizing operations of translation that comprise the sovereign power of the nation-state.

This is the limit of translation, and hence the scene of the political. With borders (limits) comes struggle. It may seem a contradiction is at work in this formulation: the subtraction within logistics of constitutive differences does not immediately lend itself to the idea of the political as the struggle with borders. Nor does such a formulation of logistics as a system of techno-social and economic practices of indifference to borders correspond with the concept of translation, which both assumes and requires difference as a condition of operation. How, then, to address the political and conceptual challenges that attend the rise of new indifferent forms of communication and governance? The erasure of constitutive differences through the biopolitical power of logistics defines the limits of translation. But the occlusion of difference should not be taken as some kind of finitude since the coding of indifference in itself multiplies the fields of distinction through the force of relations. There are and always will be relations. In this process new border struggles are comprised and the work of translation is remodulated in ways coextensive with the production of subjectivity.

The analysis of electronic waste flows serves to cleave the inter-relations of software, labour and logistics in order to identify how the indifference of communication special to logistics technology points to the limits of translation, which holds implications for biopolitical regimes of governance. The heterolingual address of translation is the analytical method that makes visible the possibility of escape from biopolitical technologies of control at work in the global logistics industry. Or, rather, the non-governable dimension of social and economic life within the electronic waste industries asserts a singular indifference to the regulatory control of logistics. This is the practice of refusal. The extent to which labour and life can withstand the encroaching predisposition of logistics as a control system par excellence is – in part – a matter of time, capital and the sovereign demand that populations comply with technologies of governance.

A study of the economies and socialities of electronic waste in China helps illuminate the political status and potential of non-governable subjects and spaces. The earlier discussion of labour and the circuits of exchange in Ningbo’s electronic waste industries are a case in point. As forms of social relation, the labour and economy in Ningbo’s e-waste industries operate outside the scope of state-corporate regimes of governance supported by logistics technologies of control. Of relevance here is the constitution of regions and the politics of translation in order to address an emerging tension of scale that extends more broadly to the global management of labour and life at play in the logistics industry. Such an analytical strategy indicates how the problematic of non-governable spaces and subjects – for better and worse – reside beyond the ‘informational sovereignty’ that imbues the biopolitical power of logistics. The social practice of translation (re)constitutes regions as they figure around the economy of electronic waste. Translation here is not so much a conscious act on the part of workers in electronic waste industries – at least not in any way that I am capable of discerning – as a social-technical relation of exteriority that arises through structural conditions and the techno-social operations of logistics software managing the movement of labour, commodities, resources and finance. What I am calling a social-technical relation of exteriority extends to the challenge of method and analysis: there is always the subject that resides beyond comprehension, that refuses to be known as such – something Gayatri Spivak carefully analyzed as the politics of the subaltern condition.

In so far as that which is perceived or manifests as non-governable – the labour and economy of electronic waste, in the case of this essay – some final points can be proffered. The spatialities of non-governable subjects constitute regions in ways that do not readily correspond with more hegemonic regional formations. Translation thus becomes a form of inventing new circuits of movement. Within such a context, regions become contested geocultural and political spaces, bringing into question the dominant understanding of regions as defined within the political-economic discourses of trade agreements, innovation and knowledge transfer and statist formations of geopolitical equivalence such as ASEAN and its expansion into ASEAN+3 (China, Japan, South Korea) and ASEAN+6 (Australia, New Zealand, India). Regions, when understood as conflictual constitutions underscored by the movements and frequently informal practices of language, culture and labour, comprise geocultural formations that seriously question the power of border technologies such as trade formations, migration and labour regimes, state alliances and global logistics. Moreover, the analytical method of translation as social practice and heterolingual address initiates a critique of sovereign power by elaborating the tensions embedded within the informal and formal dynamics of geocultural configurations. Sovereign border regimes, in other words, are brought into question with the rise of non-governable subjects and spaces associated with the social-economic life of electronic waste.

Informal circuits of exchange comprise the multiplication of economies that attend the movement of electronic waste. Such configurations may be territorial in terms of the distribution of waste, as seen for example in the intra-national or trans-regional economies of electronic waste. Within this complex of relations there is a sense in which the non-governable aspects of labour, waste and economy reside outside the biopolitical power of logistics technologies.

While this essay has concentrated on the very localized case of electronic waste in Ningbo, there are always multi-scalar dimensions and circuits that both manifest in the local and connect the local to the trans-territorial whose specificities reconfigure how the regional comes to be understood. As long as the movement and treatment of electronic waste evades the sovereign power of informatized logistics, then the connection of waste with regions remains open to the possibility of multiple configurations.

Notes

Thanks to Soenke Zehle and Brett Neilson for comments and critique of earlier drafts of this essay. The text also benefitted from questions and discussion at the Inter-Asia Cultural Typhoon Conference, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, 3-5 July, 2009.

Recent Comments