Posted: May 27th, 2010 | Author: huangyunbo | Filed under: creative industries, real-estate | No Comments »

“The severity of the pollution is not understood by either the  public or business and the situation is worsening.â€Â (Xu Qi, 2007)

1. Introduction

Creative Industries and Real Estate are normally promoted as ‘clean industries’ without the perception of pollution. However, it’s not the whole story when people within the industries showing indifference to the environment and lack of proper actions to prevent pollution, it turns out to be toxic. As Maxell and his colleagues inspire, the ‘clean’ industries can be the wasteful ones for people rely on electronic products too much which can produce toxic e-waste (Maxell, 2008a). In a following fieldwork on the relationship between the creative industries/real- estate clusters and pollution in Ningbo, the Urban-Media Network team from University of Nottingham Ningbo, China, well observed another new form of pollution in the field-Soil Contamination.

Soil contamination caused by decommissioned factories sites are rarely known neither by public nor government in China.  The sites have been widely reused in most cities in china in answering to the hot demand of land in the progress of the urbanization. Yet, the risk of contamination land has seldom been noticed and analyzed that the so called clean industries thus turn out to produce toxic clusters. Being more invisible by comparing to other pollutions such as water pollution or air pollution, this form of pollution can cause severe damage by hiding deeply under the land. The hidden polluted soil normally poses serious health and safety risks to people the environment. More seriously, some of the contaminated land might keep do harming decades even after the polluted source is moved away. Thus the bell ring for the whole society while people enjoy the creatively reuse of the suspicious abandoned factories sites.

This paper starts by raising a new question of soil pollution caused by the abandoned factories reused for creative industries and residential areas. Then by showing the link between theses ‘clean’ industries and toxic effect it can cause, cases in Ningbo and other cities in China are well demonstrating the severe risks of this hidden harm. Interviews of people with different background such as government officials from various departments, developers and environmental protection specialists also add value to the research. It’s then  followed by an emerging call to solutions and actions. This research serves as an initial attempt to increase awareness and to inspire possible strategy rather than providing detail solution for it’s not always determined by the ‘clean’ industries itself towards a better environment but the attitudes and actions taken by people within it.

2. Creative Industries is not clean: how clean industries turn out to be poisonous?

2.1 Invisible pollution

Soil Contamination, according to US Environmental Protection Agency, ‘is either solid or liquid hazardous substances mixed with the naturally occurring soil. Usually, contaminants in the soil are physically or chemically attached to soil particles, or, if they are not attached, are trapped in the small spaces between soil particles’ (USEPA, 2010)

(Suspicious Soil in Beiijiaolu, Ningbo, photo by Angela Huang)

The pollution presents risks to human health and ecosystems. It has a close link with cancers including leukaemia and neuromuscular blockage. In addition, it increases the risk to damage the central nervous system and causes headaches, nausea, fatigue, eye irritation and skin rash. Heavy metals as Lead in soil is toxic for brain damaging problems for young kids, Mercury can lead to kidney damage and cyclodienes can cause the liver toxicity. The pollution of crops grown in such contaminated soil can threaten food security and plants and animals living there therefore face the problem of safety. Soil pollution also can lead to further water pollution and air pollution (The Tropical-rainforest-animals Website, 2010)

It has been called the ‘invisible pollution’, according to Xu(2007), comparing with other forms of pollution which have visible signs such as airborne stench telling the pollution of water, soil Pollution is easier to be unnoticed. The growing danger becomes more severe in the progress of Urbanization in China today for most cities where most decommissioned factories sites without strict soil government are widely reused for building creative industries/real estate clusters

2.2 A landmine under the well-designed clusters: some facts

In the demand for urban development, China is facing steely stress in land supply in urban areas. Removing the polluted factories out of the town which are then replaced by new ‘clean’ clusters becomes a direct and easy way to solve the problem. Taking Nanjing for example, 219 polluted factories including Nanjing Chemical Plant, Nanjing Chemical Fibber Plant, Nanjing Titanium Dioxide Plant and Nanjing No.2 Steelworks have been relocated from the down town city during 1992-2006 (Public China, 2006). However, this first trend of reusing the contaminated land is really risky due to the weakness of soil government. According to an official from Environmental Protection Department, the soil contamination “does exist after the removal of polluted factories, however, this issue is now out of effective government’ (Public China, 2006). What does the official mean by ‘out of effective government’? Some facts show it’s a genuine landmine rather than an innovation of land reuse.

Lack of soil background survey

First of all, there is no mandatory law on soil background survey for land transfer in China at present. This leads to a fail in the effort to trace the history of pollution and thus cause an unclear description of responsibilities to different land users in various time. The world wide accepted principle of ‘the polluter pays’ has encountered its failure of being acclimatized to Chinese practises in the level of implement. According to Jin Weilian, governor in the Urban Construction Department of Ningbo Municipal government,  the Land and Resource Bureau (LRB) who works as the only authority to takes back the land from the polluted factories and is responsible for further planning and restructure, don’t need to convey any inspection before the land is transferred(Jin, 2010). Therefore the land without soil inspection in the stage of swapping the owners increases the uncertainty of responsibility of contamination effects. By contrast, some developed countries have improved its regulations on this aspect. In 1980‘s, when GM first entered Shanghai, recalled by Tang Shiming, an environmental Protection specialist, the company took an initiative on the soil background survey although there is now such requirement from Chinese government (Tang, 2010). Tang goes on to explains that : ‘ GM is in this way to protect itself from the risks of being complained and charged of soil contamination during the following operation in China by inspecting the land before the business starts’. It would be a long way for its Chinese counterpart to follow as Jin admitted: “It takes time for the government to consider the problem and make relevant laws†(Jin, 2010)

“The polluter pays�

Who should pay under the present administration of Chinese soil issues? The former land owner? The Land and Resource Bureau? or the new developers? And base on what? The unclear responsibility in Chinese practise makes it tough in promoting the world-wide accepted ‘Polluter Pays Principle (PPP) in dealing soil pollution. According to PPP, it requires the polluter pay for relevant prevention and control. This principle is a ‘generally recognized principle of International Environmental Law, and it is a fundamental principle of environmental policy of both the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the European Community.’ (TEE Website, 1969).  In theory, China today follows the principle in making policies on pollution prevention. However, there are some obstacles in chasing the polluters to pay during the swap of land ownership.

One of the most important reasons is there is no a specific environmental requirement for the polluters to pay for the treatment before they move from the previous sites. As China experiences a boom in the urban construction from the past 20 years, many decommissioned sites have been reused without any inspection in regarding to the soil contamination. Therefore, it becomes a tough task in promoting the PPP today years after the contamination happen for most of the polluted factories removed out of the sites are those without good financial results and most of them are broken. Even there is strong evidence that they cause pollution, they are not affordable for costly soil cleaning.

For those survival ones who might be cable to the cost have a sound  reason to refuse-there is no law in requiring them to be responsible. This leads to a review of the history of Law of Soil Prevention making. In China, according to Zhu (2010), there is no legal requirement for those factories to pay extract money if their operation is within the regulation of current environmental policies. Of course they haven’t broken the law for there is no law there actually. This strange logic helps many polluters who produce genuine pollutant escaping from the responsibility and legal punishment. Then, the decision maker must pay for it.

The Land and Resource Bureau (LRB) as mentioned is the government department who is in charge of land management. According to an interview to Xu SL (Xu, 2010), a retired officer from The Land and Resource Bureau , he said he never knows there is any requirement for land cleaning before the land transfer in his careen of 20 years in the department. The situation might change from Jan 2010 for the lesson LRB learnt in Wuhan. In a worksite accident that 3 workers severely injured due to the exposure to the soil, the developer found that the golden land it wins in a bid turns out to be toxic by soil pollution, the developer returned the land back to the government–Wuhan Land and Source Bureau who lost 12 million Chinese Yuan in the case (The Ifeng website, 2010). It might be the first story in public media that the government pay for its legal leak in contaminated land transfer which is believed to start some thoughts on reforms in soil controlling all over the countries. However it’s not always the government pay during the game of land transfer.

(The land costs LSB Wuhan 12 million, source from Ifeng.com)

In Ningbo, one high-end residential area has been built in decommissioned pharmaceutical factories that it was later found the soil is polluted and received a call for cleaning.  Interestingly enough, neither the polluter nor the LRB pay for the land treatment, but the developer. In an interview to another developer in the town, Xu (2010) said the imbalance between land supply and demand makes the developer into a dilemma that one eager to win out of other competes often the times loose the power in bargaining or to be specific speaking, the developers have no power to ask the government to compensate for the mistakes made by someone else. In this case, 8 million for the first cleaning is paid by the developer. This is easily linked with a question that why the Wuhan Developer who successfully return the land back to the government while the Ningbo one failed to. It’s simple, because the cleaning is far more expensive and out of the developer’s budget in Wuhan. More importantly, it’s known to world by media reports at that time. Consumers have sound reasons to require more ethics and responsibility from developers for consumer power is the weapon once the right are well recognized.

(The former Ningbo Pharmaceutical Factory is now reused for the most expensive residential garden, photo by Angela Huang)

Environmental Standard = Soil Standard for Human Living?

In the interview to Zhu (2010), an official of Ningbo Environmental Protection Bureau, there is a requirement for developers to pass an Environmental Evaluation Check (EEP) before any project starts. However, the evaluation is only regarding to a comparatively rough reference in environmental influence which doesn’t cover specific reference such as main heavy metals which contributed to most of soil contamination. Then if there is any reference in specifying soil standard for human health in the living environments, he answered: “we have no such kind of policy and it should be business of the Health’s Departmentâ€. Does a relevant health standard exist? It’s clearly answered by supported by Jin: “The health department has no such kind of standard (Jin, 2010). Instead, projects are supposed to be harmful less once they get the approval from the Environmental Protection Bureau.â€(Jin, 2010) This makes the basic right of safety for residence or investors on the clusters unprotected in most cities in China.

The case of Oriental Venice, one of the high-end residential areas in Ningbo, tells the damage can happen everywhere in the City every day.  Thu is discovered in the soil which resulted from improper soil cleaning by the former chemical factories (Oriental Venice Community, 2005). The discovery makes every people living in the community facing a great threat that Thu can lead to severe illness such as lung cancer. The local Environmental Protection Bureau then involve into the inspection and with a controversial result that the metal is quite few which might do no harm to human being after the polluted soil is removed. This report is not acceptable by most of the residences for they question the method the EPB uses to test the polluted area and the long-term affect Thu might cause due to those soil hidden deep under the so-called cleaned surface. The worry has sound reasons for there is no accurate standard for human health to support the saying by EPB and who can tell exactly if there is no more Thu radiation which might still affect the soil, air and water in the future. This won’t be the solo in the progress of urbanization until more people are involved in the fight to soil contamination.

(Shadow under the sunshine- The Oriental Venice Community, source from NB.focus. Com)

3. Emergent call for measures to prevent further soil contamination on decommissioned land

The management of soil pollution are therefore very weak in China. Measures should be immediately taken to stop the evil becoming worse which include public education, engagement of civil society and consumer powers, and ethical requirement for developers, law improvement, health standard setting, financial support and relevant technology.

Campaigns on public and government education will play a primary role in raising this new and unbeknown question into views of public.  As it’s well illustrated that few people including government officials or common citizen have less knowledge towards the pollution,   the education will drive more people from different levels to face and solve the problems in the near future. This strategy is a critical force from bottom up and has a close link with the consumer powers that becomes the main force to fight for their basic right of health and safety from the government and developers. This will then push the developers to join the ally no matter on their considering of the cost of the business or its reputation. Then the government is thus become the target who should take immediate actions and responsibility to deal with the pollution and to prevent further harm.

While the strategy of education is an effective way to draw attention to the issue, law making on soil pollution is the key measure to provide legal protection for future cases. According to some developed countries such as US, Australia and Holland, relevant laws have been well established. For example, US have its Soil Prevention Law in 1980. Although China starts to think of the legal improvement on soil government, according to the expert: “ The initial soil contamination law would not include specific provisions on liability or responsibility for paying for soil remediation…the law would include guidelines on risk assessment and soil remediation, as well as investigation methods and management of contaminated sites(The BNA Website, 2010). It’s thus a long way for China to go before the law is well established. However, pollution can’t wait.

Another key issue in the improvement is the setup of standards regarding soil both from Environmental Protection Bureau and Health Bureau as in China the former is in charge of environmental protection while the later is for human health issues. Thus, soil pollution has put the protection of ecology system and the health of human together that requires the coordination and a closer team work between the two departments in the future. According to Jin (2010), the success of the collaboration relies in the removal of bureaucracy among different government departments and a common consensus that avoid each does things in its own way.

Funding and Insurance can also contribute to the soil contamination solution from the financial aspects. Treating soil pollution, according to Xu (2008), is costly and more worryingly, some contamination is hard to clean completely. As Zhu argues (Zhu, 2010), some cities under developed and without sufficient financial support might make the way to land treatment tougher. The process of soil cleaning thus needs enough money to support. Special funds will be helpful in the case. In addition, the model of Insurance on soil pollution in other countries can be borrowed by the polluters to carry out contamination cleaning when the pollution inevitably happens.

Developments of soil cleaning industries and soil treating methods will decide the progress of soil pollution from technological aspects. In China, it’s a brand new market opportunity that requires sufficient expertise and technology to support. In some developed countries, the soil cleaning takes up high to 30-50% of the share of the whole environmental protection industries (The Wateruu Website, 2010). The new market will attract more foreign companies with rich soil treatment experience entering China. This might be the good news.

4. Limitation and Further research

This paper serves as the first attempt to raise the new question of soil pollution in Ningbo and other cities in China by showing some facts and proposing possible solutions. However, it’s narrowed by the sufficient source of data on soil background survey in Ningbo due to rare research and studies are made in this new phenomenon. It thus opens the door to further researches on mapping of how many polluted factories in Ningbo have been reused under the threat of soil contamination, on the accurate affect by the pollution, and professional solutions that help to prevent further damage in the future.

5. Conclusion

This paper is inspired by article Creative Industries or Wasteful Ones (Maxwell, 2010) which reveals the ‘clean’ industries might bring disaster to the world. A further research on the link between the industries and pollution in Ningbo observes soil contamination as a new form of pollution in the creative industries and real-estate clusters.

Soil pollution becomes emerging for the pollution is hidden and its affect can be long-term and fatal. The situation becomes more severe in Ningbo and other cities in China for few people now notice existence of the pollution and less report on it. Education, Law and Policies, Funding and Civil campaigns should be all involved to take immediate actions for reduction and prevention of the pollution.

As a new noticed form of damage in the progress of urbanization, soil pollution on creative industries and real estate clusters calls people’s strong awareness and proper actions towards the environment we rely on. Forget the label of Green it once have for things should be follow the logic that no clean environment, no clean industries. The bell tolls!

References

Jin, WL. (2010), Interview, 24th May, 2010.

Maxwell, Richard and Miller, Toby (2008a), ‘Creative Industries or Wasteful Ones’, Urban

China, 33:28-29, <http://orgnet.net/urban_china/maxwell_miller>, last accessed in May, 2010

Oriental Venice Community (2005),<http://nbfile.focus.cn/msgview/360337/87391570.html>,

last accessed in May 2010

Public China Website (2010), < http://www.pubchn.com/articles/8545.htm>, last accessed in

May 2010

Tang, SM. (2010), Interview, 22nd April, 2010

TEE Website (1969), Polluter Pays, < http://www.eoearth.org/article/polluter_pays_principle>

last accessed in May 2010

The BNA Website (2010), China Drafts Soil Pollution Prevention Law Based on

CERCLA, <http://ehscenter.bna.com/pic2/ehs.nsf/id/BNAP-82RCAG?OpenDocument>, last accessed in May 2010

The Ifeng Website (2010), http://finance.ifeng.com/news/house/20100304/1883612.shtml,

last accessed in May 2010

US EPA Website: <http://www.epa.gov/superfund/students/wastsite/soilspil.htm>, last

accessed in May 2010

Xu Qi (2007), Facing up to “invisible pollutionâ€,

<http://www.chinadialogue.cn/article/show/single/en/724-Facing-up-to-invisible-pollution->, last accessed in May 2010

Xu Qiang (2010), Interview, 25th May, 2010

Xu, SL. (2010), Interview, 25th May, 2010

Zhu, SF. (2010), Interview, 24th May, 2010

Posted: May 21st, 2010 | Author: lvyulin | Filed under: creative industries | Tags: creative industries | No Comments »

Introduction

The concept of “creative industries†was originally put forward in UK and has grown up in the West during 1990s (Ned, 2008: 32). Creative industries, as the UK definition describes, are “those industries which have their origin in individual creativity, skill and talent and which have a potential for wealth and job creation through the generation and exploitation of intellectual property†(DCMS 1998, cited in Keane, 2007: 4). It covers advertising, architecture, design, interacted software, film and television, music, publication, performance art, etc. (Hartley, 2005: 24). Creative industries have already played an increasingly significant role in the world economy. More than ten years later, creative industry started in China in early 2004 (Ned, 2008: 32). Nowadays creative industries are also flourishing in China, which have made a great contribution in creating fortunes and promoting other industries. Therefore Local governments in China have pressed on with the programming of creative industries. Ningbo also follows the banner of developing creative industries. And this essay will critically evaluate the development of creative industries in Ningbo. First of all, general situation of creative industries in Ningbo will be briefly presented; then some problems emerging from the development of creative industries in Ningbo will be demonstrated; further more, some suggestions for the further development of creative industries in Ningbo will be brought forward; and lastly, a conclusion will be devoted to making a general summary of the whole essay.

1. General Situation of Creative Industries in Ningbo

Harbor industries and advanced manufacturing industries have made great contributions to advance the economy of Ningbo. But recently, creative industries have played an increasingly significant role in promoting other industries and further rising the whole economy in Ningbo. In recent three years, creative industries in Ningbo have developed at a rate of 20 percent annually on average. The contributions of creative industries to the economy and society have been gradually increased, especially in creating job opportunities and expanding values of social assets. In May 2007, Ningbo Creative Industries Association was founded with the purpose of providing a good platform for probing into the ways to promote creative industries in Ningbo. (Lian, 2009: 183) By some figures and statistics, the essay will present the general situation of creative industries in Ningbo from three areas.

Industrial Design Industries: Industrial design in Ningbo has a huge market demand: in 2008, the total industrial production value was 1093.71 billion RMB, increased by 13.9 percent compared with 2006 (Lian, 2009: 183-184).

Software Outsourcing Industries: In 2007, compared with 2006, the income of software was up to 3.61 billion RMB, increased by 44.4 percent; it accounted for 1.05 percent of GDP of Ningbo compared to 0.85 percent in 2006. Its proportion in the Zhejiang province increased from 8 percent in 2006 to 10.2 percent in 2007. (Lian, 2009: 184)

Creative Industries Based on City Culture: There are nearly twenty thousand companies, more than two hundred thousand employees in this industry. The total value of the assets is up to sixty billion. In 2008, compared with 2006, the taking was 813.19 million RMB, increased by 10.07 percent. (ibid)

2. Problems of Creative Industries in Ningbo

Creative industries in Ningbo have developed by leaps and bounds, but we can not neglect the problems emerging from the progress. It is impossible to present all the problems of creative industries in the essay, therefore just two problems will be chosen to illustrate: fever of creative clusters, one in “hardware†construction, and lack of creative talents, one in “software†development.

2.1 Fever of Creative Clusters

One of the most visible measures taken by Ningbo government is to construct creative clusters, “a place for creative enterprise†(Keane, 2008), which, to some extent, improve the creative industries in Ningbo. However, there are many problems emerging in the construction of these “shining†creative clusters.

2.1.1 Lack of Overall Plans

The success of creative clusters relies highly on the good planning (Keane, 2008:35), while the construction of creative clusters in Ningbo unfortunately lacks overall plans, which is incarnated in the following three aspects.

First of all, each district plans and constructs creative cluster in its own way. In Ningbo, under the policy of developing creative industries in Ningbo, district governments independently establish their own projects of constructing creative clusters, which may cause some problems. The biggest problem is the overmuch of creative clusters. The district governments have not had the situation of Ningbo creative industries as a whole in the mind when they are planning the projects of creative clusters. It may result in the phenomenon that the supply of creative clusters ultimately exceeds the demand of the market, which would be a huge waste.

Secondly, most creative clusters in Ningbo are similar without obvious distinctions. The favoured treatments offered by different creative clusters are the same, not beyond the scope of reducing tax and rent. The target clients of these creative clusters are also the same: just “creative companiesâ€, without classification. In other words, the creative clusters in Ningbo do not have clear orientations. There are less creative clusters in Ningbo aim to attract a specific group of creative companies. Even Hefeng Originality Plaza which is known as the center of industrial design companies could admit any creative companies rather than just industrial design companies. The obscure orientations would aggravate the competition between the creative clusters in Ningbo and make against bringing the function of creative clusters into full play.

The last but not the least, in order to bloom the disused factories, some district governments in Ningbo transform these deserted plants into creative clusters, which reveals from the other side that the locations of the creative clusters are chosen without comprehensive consideration. Knowledge concentrated industries rely highly on human capital, so it is better for them to locate and centralize in the area rich of human resources (Zhang and Wang, 2008). Or creative cluster could locate in the area which has a lot of enterprises with a huge demand for product design, advertising, consultation, or other services provided by creative companies. Anyway, the locations of creative clusters should not be oriented by old plants.

2.1.2 Disused Factories as the Main Model of Creative Clusters

Many creative clusters in Ningbo are transformed from disused factories, such as 228 Creative Park, 134 Creative Valley, Loft 8, Third Factory Creative Block, etc. And more old plants are planned to be reconstructed as creative clusters. A typical example is Jiangbei district where at least 3 creative clusters are on construction whose preexistence are all deserted factories (Southeast Business). However, it is not suitable to choose old plants as bases of creative clusters.

The reasons for transforming deserted factories into creative clusters have changed from practical to superficial. In 1940s, in order to reduce the living cost, artists and designers in New York gathered in the SOHO district where the rent was low. And the SOHO district was constituted by a mass of industrial buildings which were utilized by these creative talents as their living space and working space. This is the first case of transforming disused factories into creative clusters. (Fei and Mei, 2010: 142) So originally, deserted plants were chosen to be bases of creative clusters because the constructions could offer both living and working space for creative talents and the rent there was low. Gradually the reasons have been changed. Nowadays, a large number of old factories in China have been transformed into creative clusters because some famous creative clusters abroad and success creative clusters in China, like Beijing 798 and Shanghai Binjiang Creative Park, are all built based on deserted plants. Briefly speaking, these developers of creative clusters just copy the form of some successful creative clusters, but ignoring whether it is still a good way or not in current society. Reconstructing disused industrial buildings could draw rein? Renewing deserted constructions generally costs more than building new ones (Chen, 2006: 92). Old factories could add a sense of art to the creative clusters? The range of art is extensive; different constructions have different histories and different values of art. What’s more, there is usually a potential threat accompanying disused factories: the soil pollution. Here is an instance. In 2007 some worker in Wuhan were poisoned when they were working in a building site, originally a pesticide factory there. After a series of reconnaissance and investigation, finally the result came out: the soil of this building site was badly polluted by chemical reagents. (News365) So it is possible that those creative clusters which are based on the disused factories will have some detrimental effects on people working there. Although no case has been reported in Ningbo, we should be aware of the dangers. After all, to forestall is better than to amend.

2.1.3 Not Purely Creative

Some creative clusters in Ningbo are not purely “creativeâ€, which is manifested in the following two aspects.

Firstly, creative clusters are originally constructed to gather creative companies, but some of the clusters in Ningbo actually admit any non-creative companies. With the purpose of finding out whether the creative cluster in Ningbo insist on accepting creative companies or not, I pretended to be a representative of a foreign trade company and gave calls to 5 creative clusters in Ningbo: Hefeng Originality Plaza (Ningbo Industrial Design and Creative Center), 128 Creative Park, Creative Valley, Third Factory Creative Block, and Creative 1956. The result is that Hefeng Originality Plaza and Creative 1956 both refuse to admit non-creative companies, while the rest could accept any types of companies. 128 Creative Park: non-creative companies can not directly buy but can rent the houses in the park from the house owners, which means the developers do not mind whether the cluster is creative or not after they sell out the houses; the distinction of 128 Creative park, emphasized by the receptionist there, is the “individual house†instead of other things related with creative industries; the beneficiaries of favored treatments are not limited in creative companies, but includes all the companies in the service industries. Creative Valley: non-creative companies can not directly enter the valley, however, as a receptionist there said, these companies can register a creative company to pass the government’s checkup. Third Factory Creative Block: any companies can be admitted in this block; the information given by the receptionist there is all about the acreage and rent of their houses.

Secondly, some creative clusters in Ningbo are not purely “creativeâ€, because they involve large-scale commercial estate. I will take Hefeng Originality Plaza and Book City as two examples. The former is a core demonstration area of industrial design in Ningbo, and the latter is an important part of the project “Sanjiang Culture Corridorâ€. According to the throwaway of Hefeng Originality Plaza, except for the office buildings for creative companies, Hefeng Originality Plaza also includes hotel, supermarket, KTV, cartoon cinema, book store, restaurants, fitness club, SPA house and etc. Book City is constituted by 8 buildings: a nine-floor hotel, a six-floor clubhouse, a culture & art workshop with entertainment facilities, a five-floor shopping mall, an amusement park, a media tower, a four-floor building planned for restaurants, and a book store (Southeast Business). These clusters are rather all-round commercial real-estate mixed with a creative cluster than purely creative clusters.

2.2 Lack of Creative Talents

The soul of creative industries is talents (Feng, 2009: 118). However, in Ningbo, there is a severe deficiency of talents for creative industries, like creative and technological talents, and talents in operating cultural capital and internationalizing creative industries (Ying, 2008: 26). Take industrial design as an example. There are more than 70 industrial corporations in Ningbo, but only thirty percent of them have an individual design department. Some big industrial enterprises in Ningbo, such as Fotile, Pioneer, Zhuoli, and Huayu, just have 3 to 6 designers for industrial design, and more design projects are given to other specialized industrial design companies. As for the specialized industrial design companies, the number is less than 20 in Ningbo, while there are more than one hundred companies in near Shanghai. (Lian, 2009: 197) The above phenomenon indicates, to some extent, the current situation of the absence of relevant talents in Ningbo.

The first reason for the lack of creative talents is that the creative atmosphere in Ningbo is not as pleasing as that in some metropolises like Beijing or Shanghai, so it is comparatively harder to attract creative talents from other cities (Lian, 2009: 199). Creative talents need not only the attractive treatments, but also the “circlesâ€: circle for living, circle for sociality, and circle for learning and self-promotion. But compared with metropolises, Ningbo does not have a similar creative atmosphere formed spontaneously in the course of city development; and Ningbo government neglects forming the atmosphere or creating the “circles†for creative talents when developing creative industries. Therefore, creative talents prefer to gather in the metropolises where their needs could be fully satisfied. (ibid) Another reason for the lack of creative talents is that colleges and universities in Ningbo have not paid enough attention to creative talents training, so not enough qualified creative talents have been brought up locally. Among 15 colleges and universities in Ningbo, just 4 of them have majors related to creative industries (Ying, 2008: 26-27). And take graduates in Ningbo in 2008 as an instance. There were only 72 graduates majoring in mass media, 18 in performance, 209 in art design, 51 in product design, 72 in visual art design, 86 in computer-based art design, 16 in image design, 38 in management of culture market, and 149 in cartoon design (Ying, 2008: 27). What’s more, it is impossible that all the graduates would stay in Ningbo to have jobs related to creative industries. Though Ningbo government has established a series of policies to attract and cultivate creative talents, the situation is still severe.

3. Suggestions for Creative Industries in Ningbo

After presenting the general situation and some problems of creative industries in Ningbo, the essay will enter on the suggestions for the further development. Except paying attention to the problems mentioned above, the essay will bring forward another significant point that is the protection of intellectual property which is not just for the creative industries in Ningbo, but is suitable for all the creative industries in China.

The core value of creative industries is creativity, a sort of intellectual achievement, which is invisible itself, and easily duplicated once set out to the public (Feng, 2009: 117). And intellectual property could be a means to safeguard the originality of creative achievements, and to protect the legal benefits of the creators (ibid). Therefore for creative industries, intellectual property is the core capital, and the key to survive and further develop (ibid). Currently, there are 3 laws and 2 detailed rules for intellectual property (Feng, 2009: 189). However, cases of violating intellectual properties frequently take place. Take Ningbo as an instance. In 2007, more than eight hundred cases were prosecuted in Ningbo (Lian, 2009: 197). So the government should keep on improving the existing law system of intellectual property, and sternly cracking down the behaviors of violating intellectual property. At the same time, China should strive for the voice in constituting international rules and criterions on economy and trade in order to further protect our intellectual property of our nation culture. What’s more, the public in China should be educated to have the awareness of intellectual property with the purpose of cultivating an atmosphere of respecting and protecting intellectual properties in the whole society. (Feng, 2009: 189)

4. Conclusion

To sum up, creative industries in Ningbo have developed by leaps and bounds for Ningbo has solid economic basis, advantageous geographic condition, and huge market demand. Admittedly, creative industries in Ningbo are not mature but in the early stage of development like some other cities in China. There are and would be some problems in the progress of development. It is normal and could not be avoided. As for the problems, what we should do is to face them instead of ignoring them; to solve them rather than covering them. For governments, they should not be dizzy with the attractions of creative industries; instead, they should cautiously evaluate how to properly develop creative industries on the basis of actual conditions.

References:

Chen Bochao (2006) ‘History Beginning of Shenyang Industrial Architectural Heritage and the Double Value’, Archicreation (9): 84-95.

Fei Teng, Mei Hongyuan (2010) ‘Transformation Research on Old Industrial Buildings towards Creative Industry’, Architectural Culture (1): 142-144.

Feng Mei (2009) Studies on the Development of Creative Industries in China, Beijing: Press of Economy and Science.

Hartley, John (2005) ‘Creative Industries’, in J. Hartley (ed.) Creative Industries, Oxford: Blackwell, pp.1-31.

Keane, Michael (2007) Created in China: The Great New Leap Forward, London: Routledge.

Keane, Michael (2008) ‘Creative Clusters: Out of Nowhere?’, Urban China 33: 34-35.

Lian weijia (2009) ‘Strong Market Demands Drive the Development of Creative Industries in Ningbo’, in Zhang Jingcheng (ed.) 2009 Chinese Creative Industries Report, Beijing: China Economic Publishing House, pp. 182-204.

Ned, Rossiter (2008) ‘Informational Geographies vs. Creative Clusters’, Urban China 33: 32.

News 365 (2010) http://nwes365.com.cn Last accessed May 2010.

Southeast Business (2010) http://dnsb.cnnb.com.cn Last accessed May 2010.

Ying Jinping (2008) ‘On the Cultivation of Talents in Cultural Industry in Ningbo’, Journal of Zhejiang Business Technology Institute 7 (4): 25-28.

Zhang Meiqing, Wang Lijun (2008) ‘Investigation and Analysis on Creative Industry Cluster’. http://www.seiofbluemountain.com/upload Last accessed May 2010.

Posted: May 21st, 2010 | Author: yangwu | Filed under: creative industries, real-estate | No Comments »

– To what extent the Culture & Creative Industries server for the Commercial &Real Estate Industries, taking Ningbo experience as an Example

Introduction

A big Chinese character “chai†(plan to be demolished) marked on the wall of the ruins, the gone bulldozer leaving a cloudy of dust behind; one and another aged building crashed to the ground in second, these pictures are frequent to be seen in the contemporary China. However, it seems that some old plants are lucky to survive from the destiny of demolition. Given the rise of the creative industries and the influential practices in the western countries, Chinese government learned from the profound strategies to urban development and started driving on the creative industries in the name of protecting and revaluing the heritage of the historic manufacture time.

The concept of the creative industries was initially introduced and highly promoted in UK from 1990s. It is a type of industries identified with the transfer to knowledge economy and the generation of creativity-based high value-added products and services. Although, UK is the first one raising the concept of creative industries, the orinigal artist community or more appropriately the sample artist creative cluster could be traced back to 1960s in America, for instance, SOHO region (Zukin 1989). The historic transformation of SOHO region presented an accidental outcome of stimulating the real estate market by its LOFT workshop and lifestyle bringing about the culture consumption by the middle-class (ibid). The same byproduct effect could be found in Beijing 798 art district as well (Berghuis 2008).

Motivated by its potential political, economic, social benefits, the development of creative industries was listed onto the agenda of China’s 11th Five Year Plan in 2005 (Rossiter 2008). However, other than generating economic power, the Chinese experience seems more focused on using creative industries to support real estate industries, commercial industries and tourism industries, moreover, to attract a large number of capital flows. More critical suspicion uttered by MyCreativity is that,

“…investment in ‘creative clusters’ effectively functions to encourage a corresponding boom in adjacent real estate markets. Here lies perhaps the core truth of the creative industries: the creative industries are a service industry, one in which state investment in ‘high culture’ shifts to a form of welfarism for property developers.â€(Rossiter et al 2006: 242).

This essay will investigate the relation intertwined between creative industries, urban space production, and real estate industries. Starting with relevant literature reviews, a closer look will be shed on the discourse of creative cluster, and deconstruct the creative cluster to two parts through more thoughtful interpretation. Then it will question a major problem within the creative cluster on its intensified interest in geographical location or physical property dimension. In final, the main argument will be explained through the field work in Ningbo account and the core fact is that, through adopting the creative industries strategy, local government, and urban planners join force with the land developers and the capital investors to start another round of urban renewal.

1 Cultural Creative Industries and Urban Development

As noted before, the creative industries was initially introduced in the early 1990s, identified as a new information besed economy. According to the report issued by Creative Industries Task Force (DCMS 2001:4), the creative industries is defined as “activities which have their origin in individual creativity, skills and talent, and which have the potential for wealth and job creation through generation and exploitation of intellectual property.†Along with the rapid development of Internet and media technologies and its global proliferation started in the same period, it lit up the universal enthusiasm for this new type industry (Flew 2009). Moreover, its low costs of production for one hand makes more competitive; on the other hand, it brings local industries moving upwards in the global value chain.

The connections between the rise of the creative industries and the development of cities were later drawn into the discussion. In the 1979s and 1980s, the cities in most western countries were suffering from the decline of manufacturing industries and encountering a bottleneck of development (Flew 2009:85). With the emergence of the creative industries, urban planners grasped the opportunities to using information economy as urban renewal strategies, highlighting the culture and creativity as a powerful means to revitalize and modernize parts of its urban economy. Meanwhile, many scholars joined to back up the cooperation between the creative industries and the urban regeneration. Scott (2008, see in Flew 2010) related the rise of creative economy to the resurgence of cities. And other scholar like Landry (2000) termed the cities as the hard infrastructure of creative industries, able to provide sufficient facilitates and relevant service network as well.

1.1 The Rise of Creative Industries in China

In late 2004, the concept of the creative industries arrived in mainland China. It was firstly adopted into practices by the cities like Shanghai and Beijing (Keane 2009a). Later on, the creative industries were officially put on the agenda in the 11th Five Year Plan from 2005 by PRC government (Rossiter 2008). An important goal is the ambition to switch the current China reality of ‘Made in China’ to ‘Create in China’, and thus to move higher up the value chain from the bottom position to upward (ibid). Since then, to accordingly promote creative economy, the officials, scholars, practitioners, entrepreneurs and developers have exploited the idea of creative industries and a range of Creative Cluster, Creative Harbor, Innovation Park and High-Tech Zone were springing up like mushroom largely in the mainland China.

In one of Keane’s reports, the author has done some ground investigation of creative clusters in Suzhou and Foshan. The purpose was to look into the underlying constraints within China’s creative economy (Keane 2009b). He argues that the example accounts and the vast majority of data together draw a conclusion that China’s creative industries are fundamentally misunderstood in China and more appropriately the cultural industries. By adopting the mode of cultural industries, it drives local urban development and increases land values conspiratorially (ibid).

1.2 The Reproduction of Space: From Retired Plant Building to New Creative Cluster

When the manufacturing industries moved out from the downtown city, those plant sites and retired buildings had to encounter an uneasy fate. Urban renewal project set up a target for new modern appearances instead of old historic ruins. As a result, many old industrial buildings of the city could only keep their memories into the city museum archives. After years’ urban development, a result is that China has received a bad reputation for destroying its historical roots as well as demolishing every old building.

Noticing that the rapid development of the creative industries in the western countries, gradually the urban planners realize that rather than absolute demolition it is possible to effectively repackage those old industrial buildings into the creative industries clusters, so as to rekindle the vitality of the original site and receive the same outcome as the former way of demolition. Soon, local governments and urban planners joining force with the land developers and the capital investors start another round of urban renewal through adopting the creative industries strategies.

2 Clustered Creative Industries and Real Estate Industries

Pasquinelli revisits David Harvey’s work of The Art of Rent (Harvey 2001), claiming that “all the immaterial economies have a material, parallel counterpart where the big money is exchanged†(2006:22). The mode of value generation in creative industries domain is in fact not limited to the exploitation of intellectual property, but also a more tendentious way of parasitic exploitation by another material objects. The discourse “collective symbolic capital†introduced by Harvey unveils the potential political economy of cultural interventions and the parasite exploiting the social creativity. The culture context provides the marks of distinction which be exploited further by capitalists to sell material goods. Pasquinelli states that the production of culture as social capital and real estate speculation is a couple of immaterial and material compound (ibid). Therefore, inspired by Pasquinelli’s argument, we try to decode the discourse of the creative industries into two parts: the culture and creativity as immaterial part; the clustered territory as material part.

2.1 The Culture and Creativity

Firstly, we draw on one of its subordinated elements: the culture and creativity. In his book The Rise of Creative Class, Richard Florida argued that “Creativity has come to be the most highly prized commodity in our economy†(2002:5). It also introduces a newly emerged social class as the “Creative Class†referring to those both being the source of “Creativity†in the rise of Creative Industries and contributing to the consumption for generating the economic growth in the cities; it seems a positive and productive circle. So, Florida argues that city’s economic prosperity and cultural attractiveness would increasingly depend on how the “Creative Class†is attracted and kept by the local strategies (ibid).

2.2 The Clustered Space

Another key element is concerning the cluster phenomenon. It is noted that the first interest to promote a cluster mode can be dated back to late 19th century. A British economist Alfred Marshall suggested the positive outcomes by clustering the related firms and industries to build a value chain (See in Flew 2010). Then in one decade later, another theorist Michael Porter put into effort to readdress the benefits of cluster as a business management mode (ibid).

Porter (1998) analyzed the cluster mode would bring about at least three competitive advantages to the involved industries, namely productivity gains, innovation opportunities, and new business formation. The first advantage refers to specialist inputs and skilled labor, enabling to promote the professional reputation and strengthen the collective power. The second one of innovation opportunities is focusing on the interaction with buyers and suppliers by emerging a present and compact value chain. The third one of new business formation is derived from better access to resource, such as venture capitalist, skilled workforce (See in Flew 2010:86-87). This notable cluster theory encourages the model of cluster spreading around. As noted earlier, other conceptual literatures have shed the light on spatial agglomeration and confirmed its capability to smooth the flexibility of information flows, interactive network and relation ties among the diverse but relevant industries (Scott et al 2001).

Taking account of above cluster characteristics, the urban policy makers in the stage of postindustrial cities began to combine the culture-led urban regeneration and the cluster mode (Schuster 2002). Practical cases like Hollywood and Silicon Valley demonstrate well the application of creative cluster theory. Except the initial startup in western countries, it also seems to find an even consistent role in countries like China where a collectivist ethos has long been cultivated by the state ideologies (Keane 2009a).

2.3 The Transfer: From Cultural Creative Cluster to Commercial Real Estate Industries

Summarized by Borg, Tuijl and Costa in their working report of creative industries in relation with Beijing urban development experience, there are at least two types of creative clusters: artists creative clusters and commercial creative clusters (2010:6). The artists creative clusters appear and grow ‘spontaneously’ by initiatives of artists who concentrate in a certain area to benefit from shared specialized field and inspiring artist environment. Differently, the commercial creative clusters are driven by real estate speculations and are much more planned, focusing on commercial spin-offs of art and culture. However, to name the representatives of the both, the artist creative cluster could refer to the original 798 art district; another type again could refer to 798 art district but in a later phase. In the same report, it records that through the transformation from artist creative cluster to commercial creative cluster, the most conspicuous difference is the growth of real estate price. Furthermore, the increasingly energetic commercial activities have also a profound effect in the form of rising rents. Some of the artists can’t afford the higher rents and have to move out of the area (ibid).

The familiar argument could be seen from Berghuis’ account of Dashanzi art district (2008). He argues that the most fundamental and essential development occurring here is indeed the real estate industry more than a contemporary art cluster Though, the place like Dashanzi district started as an experimental art basement of artists’ initiative, but it now ends up a trendy cultural cluster and commercial district whose biggest beneficiaries are property dealers. The loser could be the artists who contributed to the reborn of 798 art factory but eventually have to be driven off by the increasingly raised residential rent. In fact, the distinct culture context or creativity brand helps promoting the real estate speculation and generates a compound economy of creative industries and commercial industries (ibid).

3 Leading Actor or Supporting Actor

Following up the topic on the creative industries in relation to urban space production, this section scheduled to reflect forementioned literature thoughts into the performance of Ningbo creative industries in reality. The argument embedded is that the creative industries, for one hand, is a set of economic form, expected to generate economic growth and contribute to labor employment; on the other hand, it is also a tool, used to cover the underneath strategies for coalition between local government, real estate developer and commercial industries. We have chosen three observation sites for field work and systematically picked them up per differentiated phase categories. Phase one means the planning settled down and the project under construction; phase two refers to nearly finished project on a trial run; the phase three suggests the project formally on business.

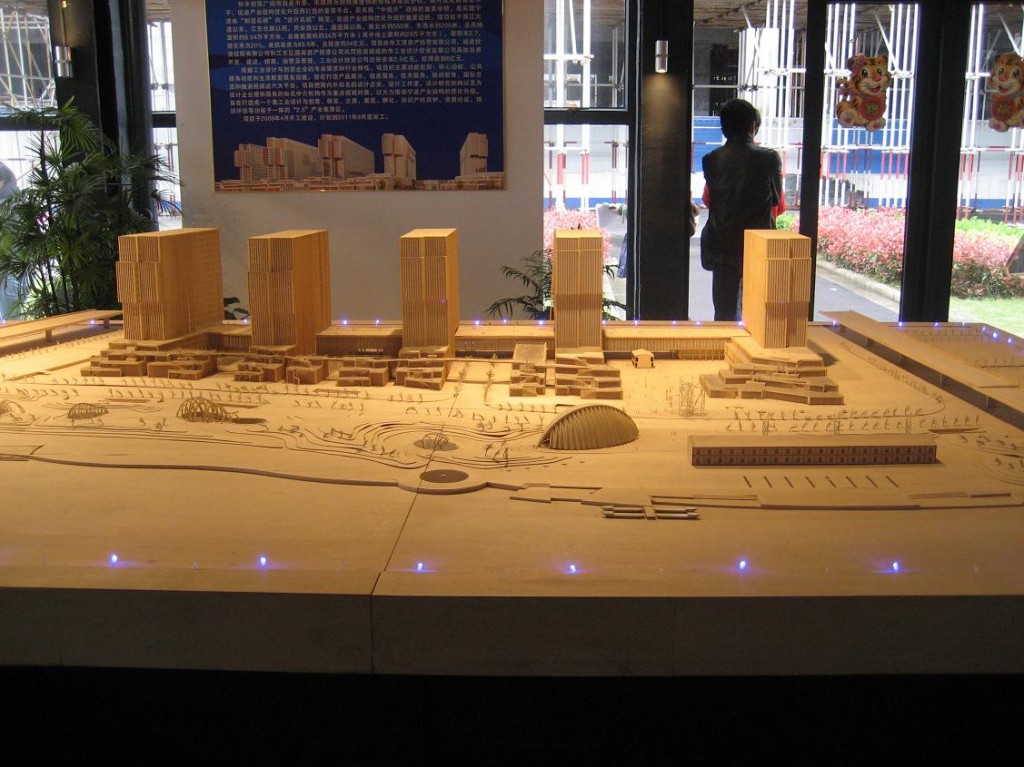

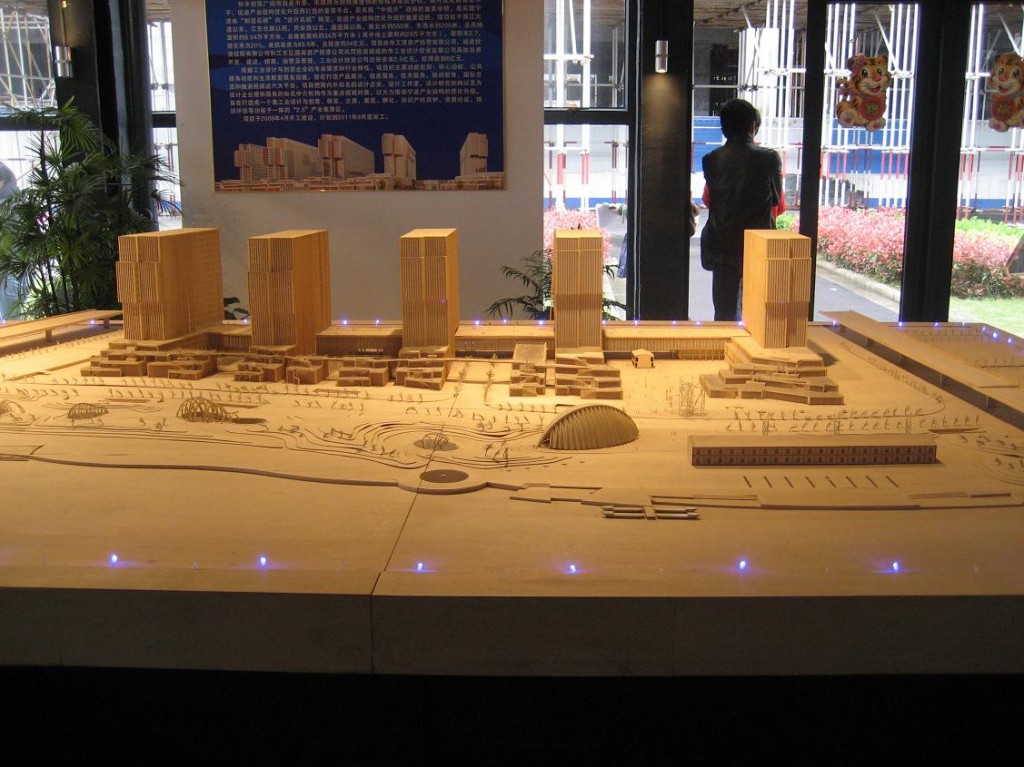

3.1 Phase one: Hefeng Creative Square

The first observation spot is Hefeng Creative Square, located in the east bank of Yao River. Though only semi-finished architectural complex erects on site, the temporary enclosure wall presents impressive advertisements to attract potential companies and financial investment. Learned from the interview, the ambition of Hefeng is to establish a flagship industry in providing creative and innovative service to plenty manufactories in Ningbo area, not only compete with local service providers, but also those from Shanghai or others, even foreign countries. In regards with the decisive advantage for them to compete with other creative clusters, the interviewee emphasized the professional guide and training provided by cluster committee plus the golden location, the center of downtown Ningbo.

(Picture No.1: The Planning Map of Hefeng Creative Square)

The planning map demonstrates the square with a large plot in territory. Moreover, Hefeng creative square is not positioned as a simplex creative cluster, but integrated with commercial-oriented use like restaurants, hotel, shopping centre, and entertainment. The mode refers to the urban planner’s additional proposal that, besides the creative industries, they also conspire to develop real estate industries, commercial industries and tourism industries as well.

3.2 Phase two: Book City

The second spot is Book City. It is one of key culture and creative projects promoted by Ningbo Government. Situated oppositely to Ningbo Laowaitan, the site was once the flour factory of Ningbo. As same as Hefeng Creative Square, the structure of Book City is weaved as a matrix bonded culture and creative industries with commercial industries. The project of Book City is near to completion, and the key building which is the biggest one just celebrated its opening to public. To brand its culture meaning, Book City is titled as “City Reading Room on East Bank of Yong River †(CNNB 2010); for commercial promotion, it again advertise with “The First Culture, Tourism, and Commercial Plaza on Mouth of Three River†( Book City Billboard 2010, pic 2).

(Picture No.2: The Billboard Advertisement of Book City)

Since it is partially launched on business, we arrived at the site and did some anthropologist investigation. Next to Book City there is one normal-leveled residential community, so most retails around are accordingly small and simple ones including clothing shops, convenient stores and casual eating places. However, the propaganda of Book City promotes that the street beside will be the city’s future culture corridor. The most immediate effect observed on site is that some shops are closed for redecoration (maybe to upgrade); some change the business types. Moreover, we randomly interviewed some shop owners, some of them are optimistic about the benefits bought by Book City, for example, the existing restaurants; some complained the increased rent, such as low priced clothing shops.

In the case of Book City, the finding is to some extent the evidence to Keane’s argument that the Chinese experience of Creative Industries is mostly the Culture Industries (2009b). To decode the culture and creativity in a semiotic approach, these old buildings and old plants while transforming to the culture and creative cluster, it has become the visible imaginary symbols of the city culture and social experience.

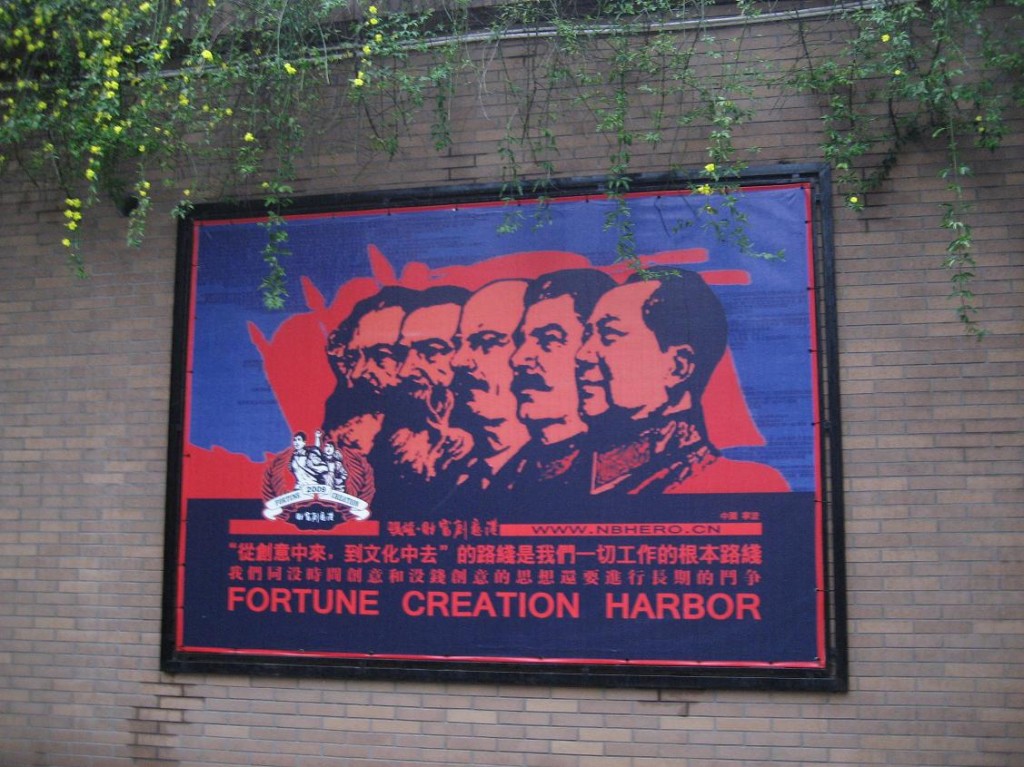

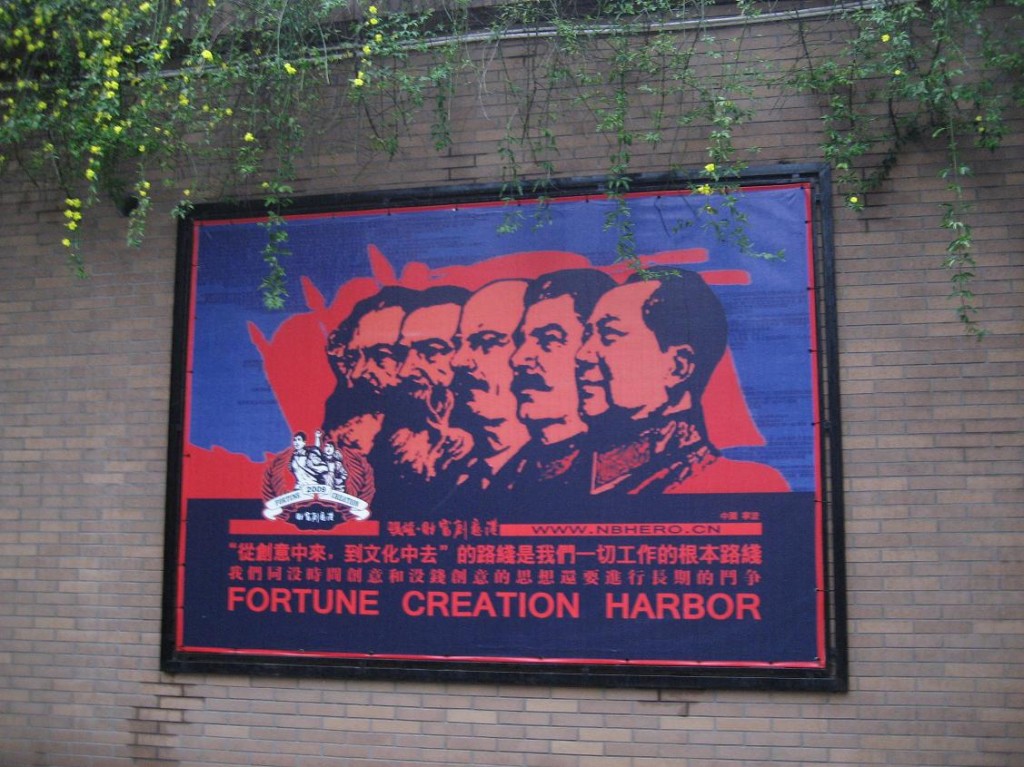

3.3 Phase three: Fortune Creation Harbor

(Picture No.3: The Billboard Culture of Fortune Creation Harbor)

The last observation site is Fortune Creation Harbor situated in the North Bank Fortune Centre near to Ningbo Great Theater. At a first sight of the North Bank Fortune Centre, we noticed that though it covers huge territory with several high-end complexes, some offices seem empty and few pedestrians could be observed on site. When we get close to Fortune Creation Harbor, the situation is exactly the same, some companies removed out, some with no clue or little connection with creative industries.

Referencing to the initial design of Fortune Creation Harbor, it was once a key creative industries project promoted aggressively by Jiangbei government. The third picture attached above should have witnessed the prosperity once upon the time. However, two year later, the place shows more deserted and silent. It has failed to live up to the ambitions of their planners. We assume that this concerns much with the planner’s strategies for positioning the place. The basic mode is the same as of Hefeng Creative Square and Book City, to establish a comprehensive industries center, and the aim is to present a perfect package for attraction from real estate speculators and capital investor. Backed up by conspicuous state investments and by fast decision making, the areas have been transformed and neighborhoods have been revitalized, infrastructure has been upgraded. Unfortunately, a great leap forward can not guarantee a long term benefit.

Conclusion

In conclusion, to apply the concept of parasitic exploitation of symbolic capital (Pasquinelli 2006), the mode of development of creative clusters in local Ningbo seems a contradictory and conflicted. It confirms the situation of Ningbo’s creative industries that the culture and creative economy-oriented project is possibly exploited mostly by real estate speculators and leave little space for sustainable development of culture and creative reproduction.

Using the creative industries as overwrap, and then packaging the commercial oriented industries into creative economics, such a development mode of creative industries was copied by a lot of followers. As in Ningbo area, we’ve observed Loft8, Creation harbor and Creative 3rd plant established one and another designed in similar way. In a first sight, such creative industries may bring instant benefit as it successfully promotes the real estate speculation. However, the more in-depth and profound effect should be questioned and highlighted: how long could this mode of “fake†creative industries further go?

References

Berghuis, T, J(2008), ‘Constructing The Real (E)state of Chinese Contemporary Art: Reflections on 798, in 2004′ , Urban China 33 [Special Issue: ‘Creative China: Counter-Mapping Creative Industries’].

Borg, J, Tuijl, E and Costa, A, 2010, Designing the Dragon or does the Dragon Design? An Analysis of the Impact of the Creative Industry on the Process of Urban Development of Beijing, China, Retrieved May, 2010 from

http://www.dse.unive.it/fileadmin/templates/dse/wp/WP_2010/WP_DSE_borg_tuijl_costa_03_10.pdf

CNNC,2010. Special Website for Book City, Retrieved May, 2010 from

http://zt.cnnb.com.cn/system/2010/04/23/006500222.shtml

DCMS (2001), Creative Industries Mapping Document 2001 (2 ed.), London, UK: Department of Culture, Media and Sport, Retrieved May, 2010 from http://www.culture.gov.uk/reference_library/publications/4632.asp

Flew, T. 2009. ‘The cultural economy moment?’ Cultural Science. Retrieved May, 2010 from http://cultural-science.org/journal/index.php/culturalscience/article/view/23/79

Flew, T. 2010. ‘Toward a Cultural Economic Geography of Creative Industries and Urban Development: Introduction to the Special Issue on Creative Industries and Urban Development’, The Information Society, 26: 2, 85 – 91. Retrieved May, 2010 from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01972240903562704

Florida, R. 2003 The Rise of the Creative Class. New York: Basic Books

Harvey, D. 2001, ‘The Art of Rent: Globalization and the Commodification of Culture’, in Spaces of Capital: Towards a Critical Geography, New York: Routledge, 2001, pp. 394-411

Keane, M. 2009a ‘Creative industries in China: four perspectives on social transformation’, International Journal of Cultural Policy, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 431–443

Keane, M 2009b ‘Understanding the creative economy: a tale of two cities clusters’. Creative Industries Journal, 1(3). pp. 211-226.

Landry, C. 2000. The creative city: A toolkit for urban innovators. London: Earthscan

Lovink, G and Rossiter, N (eds) 2006, ‘MyCreativity: Convention on International Creative Industries Research’, MyCreativity Reader: Critique of Creative Industries, Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, pp. 241-247.

Pasquinelli, Matteo (2007) ‘ICW-Immaterial Civil War, Prototypes of conflict within cognitive capitalism’, in Geert Lovink and Ned Rossiter (eds) MyCreativity Reader: Critique of Creative Industries, Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, pp. 71-81.

Porter, M. 1998. ‘Clusters and the new economics of competition’. Harvard Business Review 76:77–91.

Rossiter, N. 2008, Counter-mapping Creative Industries in Beijing (Introduction), Urban China, No. 33, December 2008

Schuster, J 2002. ‘Sub-national cultural policy—Where the action is? Mapping state cultural policy in the United States’. International Journal of Cultural Policy 8:181–96

Scott, A,J (ed) 2001. ‘Global city-regions’. In Global city-regions: Trends, theory, policy, pp11–30. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scott, A. J 2008. Social economy of the metropolis: Cognitive-cultural capitalism and the global resurgence of cities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zukin,S 1989. Loft Living Culture and Capital in Urban Change. Rutgers University Press

Posted: May 13th, 2010 | Author: yangwu | Filed under: creative industries, real-estate, video | No Comments »

This documentary follows the topic on the Creative Industries in relation to urban reconstruction and land development. In the process of Ningbo’s city development and urban renewal in the recent years, one would witness that the Creative Industries plays an active and significant role and potentially processes economic, political or social power.

The argument embedded in the documentary is that the Creative Industries, for one hand, is a set of economic form, able to generate economic growth and contribute to labor employment; on the other hand, it is also a tool, used to cover the underneath strategies for coalition between local government, real estate developer and commercial industries.

In order to visually present the argument and demonstrate it in a convinced and easily understood way, the project of Book City is selected as an example for assessment.

Here is the documentary, enjoy~~

Posted: May 13th, 2010 | Author: huangyunbo | Filed under: creative industries, real-estate, video | No Comments »

This documentary is inspired by the lecture on ‘waste industries:Secondary Resources and the Geopolitics of Waste Distribution’ which reveals the unknown relationship between the Creative Industries with an image of being ‘clean’ and how it ‘contribute’ to a toxic industry of E-Waste.  Further field works on Creative industries and Real Estate Industries made a new observation  that new soil pollution due to the clusters built on decommissioned factories sites without proper cleaning once again make the ‘clean industries’ into a toxic ones.Â

The documentary serves as a recorder that  traces the research from realizing the toxic side of a ‘clean’ industry to  field trips in finding the local discourses(Soil Cleaning due to the change of land ownership is normally ignored by local government, developers and even the consumers).  The aim of the research is not to find out answer on  whether the so-call clean industries is clean or not,  is with an effort to find out the relationships with which local practices can be tested by the academic inputs(why should soil cleaning be treated seriously, for whom? and who can contribute to a better solution?..etc.).

By identifying the above questions , a further attempt will be made to reveal and solve the problems  in a following essay with the same title.

Clean Industries, Toxic Clusters

Posted: April 26th, 2010 | Author: lvyulin | Filed under: creative industries | Tags: creative industries | No Comments »

On 2nd April 2010, the Urban-Media Networks team carried out a fieldwork to find out more about the current situation of creative industries in Ningbo. The two destinations selected are Hefeng Originality Plaza (Ningbo Industrial Design and Creative Center) and Fortune Creation Harbor.

Hefeng Originality Plaza is one of the most important projects initiated by the government to promote creative industries in Ningbo. It has both financial assistance and policy support from Ningbo government. This plaza is not merely a creative cluster, but also includes a hotel, a shopping center, restaurants, and other entertainment facilities. The target clients of these establishments, as one of the staff in the Hefeng Originality Plaza said, are those regarded as middle-class with large amount of private property and relevant consumer habits, while the migrant workers constructing the plaza are absolutely excluded.

Fortune Creation Harbor, as a creative cluster, is not so successful just like other team members description. But it is a little unfair to say that it is a failure example of creative clusters for there are indeed some creative companies like advertising companies and art design centers; and it is also unfair to compare Fortune Creation Harbor with Hefeng Originality Plaza because the former one has already finished the construction, while the latter one is still on construction, and challenges sometimes emerge after construction, just like most problems appear after marriage. So it is a little early to praise Hefeng Originality Plaza, and to deny Fortune Creation Harbor as a creative cluster.

Posted: April 26th, 2010 | Author: lvyulin | Filed under: creative industries | No Comments »

It seems that creative industries are not as green as supposed. E-waste has been a shadow of the “clean†creative industries. Obviously, people who deal with e-waste, like those in Lùqiáo Qū and Gùiyǔ, are the victims in creative industries developments, sacrificing their and even future generation’s health and natural environment. People exposed to e-waste have higher risks to catch diseases of vital organs; Contaminants saturate the soil, rivers, and air, and spread to the surrounding villages. However, if there are no effective ways put forward to deal with e-waste, victims will not just limited to this specific group, but all the people in the world, as we share the same globe.

Posted: April 26th, 2010 | Author: lvyulin | Filed under: creative industries | Tags: creative industries | No Comments »

This article lists three important developments in terms of migratory movement in China. As an instance raised by author, the demolition of the hutongs in Beijing, behind which creative industries are an important factor, reminds me something I forgot before. The original place Ningbo Hefeng Originality Plaza (Ningbo Industrial Design and Creative Center) located included not only a cotton mill, but also a resident area where my aunt had lived for more than ten years. The house my aunt lived with other families is a Qing dynasty two-floor architecture with delicate carving on the ridge beams. It is not the only one in this resident area. Regrettably, they were demolished in 2001. What a strong will the government has to renew urban districts!

Posted: April 26th, 2010 | Author: lvyulin | Filed under: creative industries | Tags: creative industries | No Comments »

One of the most impressive points in this article is the emphasis on “catch-up learning†which involves a process of “unlearning†and further exceeding of the codified knowledge with the purpose of achieving generative growth (Keane, 2008:35). Accordingly, unnecessarily duplicating the existing successful models from other cities or carrying out ‘follow-the leader’ strategies could not help to advance the competitive power of creative industries in China. For example, the success of Beijing 798 and Shanghai Binjiang Creative Park, both built based on deserted plants, has led to the phenomenon that a large number of old factories in China have been transformed into creative clusters. A typical instance is Hangzhou where at least eight creative clusters are originally old factories, like Loft 49, A8 Art Community, Tangshang 433, and 177 Creative Park. Even the names of these creative clusters are similar as Beijing 798, entitled by numbers. What’s more, there are more than one hundred old plants have been renewed as creative clusters. Although the retooling of factories as creative industries “has clear effects upon the texture of the urban landscape†(Neilson, 2008: 42), there are still some questions need to be further studied: are these factories suitable to be transformed into creative clusters? Is it the best way to build a creative cluster on the basis of a deserted plant? Is building creative clusters the best way to promote creative industries? Could a satisfying return be got from building this kind of creative clusters? Admittedly, it is necessary for us to learn from other cities’ experience at the very start, but more significantly we should identify our own advantages in the through knowledge accumulation and innovative thinking (Keane, 2008:35) instead of just copying the successful models and neglecting whether it is suitable or not.

References:

Keane, Michael (2008) ‘Creative Clusters: Out of Nowhere?’, Urban China 33: 34-35.

Neilson, Brett (2008) ‘Labour, Migration, Creative Industries, Risk’, Urban China 33: 42-43.

Posted: April 25th, 2010 | Author: yangwu | Filed under: creative industries, real-estate | No Comments »

In the article, Pasquinelli revisits David Harvey’s work of The Art of Rent (Harvey 2001), claiming that “all the immaterial economies have a material, parallel counterpart where the big money is exchanged†(Pasquinelli 2006: 22). The mode of value generation in creative industries domain is in fact not limited to the exploitation of intellectual property, but also a more tendentious way of parasitic exploitation by another material objects. The discourse “collective symbolic capital†introduced by Harvey unveils the potential political economy of cultural interventions and the parasite exploiting the social creativity.

The culture context provides the marks of distinction which be exploited further by capitalists to sell material goods. The article mentions the Barcelona city as an example; Pasquinelli states that the production of culture as social capital and real estate speculation is a couple of immaterial and material compound.

To apply the concept of parasitic exploitation of symbolic capital, the mode of development of creative clusters in local Ningbo seems a contradictory and conflicted circumstance for further investigation. An initial thought of this phenomenon is that the culture and creative economy-oriented project is possibly exploited mostly by real estate speculators and leave little space for sustainable development of culture and creative reproduction.

References:

Harvey, David (2001), ‘The Art of Rent: Globalization and the Commodification of Culture’, in Spaces of Capital: Towards a Critical Geography, New York: Routledge, 2001, pp. 394-411

Pasquinelli, Matteo (2007) ‘ICW-Immaterial Civil War, Prototypes of conflict within cognitive capitalism’, in Geert Lovink and Ned Rossiter (eds) MyCreativity Reader: Critique of Creative Industries, Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, pp. 71-81.

Recent Comments