Cluster as Material, Creativity as Cover, Real Estate as Conspiracy

Posted: May 21st, 2010 | Author: yangwu | Filed under: creative industries, real-estate | No Comments »– To what extent the Culture & Creative Industries server for the Commercial &Real Estate Industries, taking Ningbo experience as an Example

Introduction

A big Chinese character “chai†(plan to be demolished) marked on the wall of the ruins, the gone bulldozer leaving a cloudy of dust behind; one and another aged building crashed to the ground in second, these pictures are frequent to be seen in the contemporary China. However, it seems that some old plants are lucky to survive from the destiny of demolition. Given the rise of the creative industries and the influential practices in the western countries, Chinese government learned from the profound strategies to urban development and started driving on the creative industries in the name of protecting and revaluing the heritage of the historic manufacture time.

The concept of the creative industries was initially introduced and highly promoted in UK from 1990s. It is a type of industries identified with the transfer to knowledge economy and the generation of creativity-based high value-added products and services. Although, UK is the first one raising the concept of creative industries, the orinigal artist community or more appropriately the sample artist creative cluster could be traced back to 1960s in America, for instance, SOHO region (Zukin 1989). The historic transformation of SOHO region presented an accidental outcome of stimulating the real estate market by its LOFT workshop and lifestyle bringing about the culture consumption by the middle-class (ibid). The same byproduct effect could be found in Beijing 798 art district as well (Berghuis 2008).

Motivated by its potential political, economic, social benefits, the development of creative industries was listed onto the agenda of China’s 11th Five Year Plan in 2005 (Rossiter 2008). However, other than generating economic power, the Chinese experience seems more focused on using creative industries to support real estate industries, commercial industries and tourism industries, moreover, to attract a large number of capital flows. More critical suspicion uttered by MyCreativity is that,

“…investment in ‘creative clusters’ effectively functions to encourage a corresponding boom in adjacent real estate markets. Here lies perhaps the core truth of the creative industries: the creative industries are a service industry, one in which state investment in ‘high culture’ shifts to a form of welfarism for property developers.â€(Rossiter et al 2006: 242).

This essay will investigate the relation intertwined between creative industries, urban space production, and real estate industries. Starting with relevant literature reviews, a closer look will be shed on the discourse of creative cluster, and deconstruct the creative cluster to two parts through more thoughtful interpretation. Then it will question a major problem within the creative cluster on its intensified interest in geographical location or physical property dimension. In final, the main argument will be explained through the field work in Ningbo account and the core fact is that, through adopting the creative industries strategy, local government, and urban planners join force with the land developers and the capital investors to start another round of urban renewal.

1 Cultural Creative Industries and Urban Development

As noted before, the creative industries was initially introduced in the early 1990s, identified as a new information besed economy. According to the report issued by Creative Industries Task Force (DCMS 2001:4), the creative industries is defined as “activities which have their origin in individual creativity, skills and talent, and which have the potential for wealth and job creation through generation and exploitation of intellectual property.†Along with the rapid development of Internet and media technologies and its global proliferation started in the same period, it lit up the universal enthusiasm for this new type industry (Flew 2009). Moreover, its low costs of production for one hand makes more competitive; on the other hand, it brings local industries moving upwards in the global value chain.

The connections between the rise of the creative industries and the development of cities were later drawn into the discussion. In the 1979s and 1980s, the cities in most western countries were suffering from the decline of manufacturing industries and encountering a bottleneck of development (Flew 2009:85). With the emergence of the creative industries, urban planners grasped the opportunities to using information economy as urban renewal strategies, highlighting the culture and creativity as a powerful means to revitalize and modernize parts of its urban economy. Meanwhile, many scholars joined to back up the cooperation between the creative industries and the urban regeneration. Scott (2008, see in Flew 2010) related the rise of creative economy to the resurgence of cities. And other scholar like Landry (2000) termed the cities as the hard infrastructure of creative industries, able to provide sufficient facilitates and relevant service network as well.

1.1 The Rise of Creative Industries in China

In late 2004, the concept of the creative industries arrived in mainland China. It was firstly adopted into practices by the cities like Shanghai and Beijing (Keane 2009a). Later on, the creative industries were officially put on the agenda in the 11th Five Year Plan from 2005 by PRC government (Rossiter 2008). An important goal is the ambition to switch the current China reality of ‘Made in China’ to ‘Create in China’, and thus to move higher up the value chain from the bottom position to upward (ibid). Since then, to accordingly promote creative economy, the officials, scholars, practitioners, entrepreneurs and developers have exploited the idea of creative industries and a range of Creative Cluster, Creative Harbor, Innovation Park and High-Tech Zone were springing up like mushroom largely in the mainland China.

In one of Keane’s reports, the author has done some ground investigation of creative clusters in Suzhou and Foshan. The purpose was to look into the underlying constraints within China’s creative economy (Keane 2009b). He argues that the example accounts and the vast majority of data together draw a conclusion that China’s creative industries are fundamentally misunderstood in China and more appropriately the cultural industries. By adopting the mode of cultural industries, it drives local urban development and increases land values conspiratorially (ibid).

1.2 The Reproduction of Space: From Retired Plant Building to New Creative Cluster

When the manufacturing industries moved out from the downtown city, those plant sites and retired buildings had to encounter an uneasy fate. Urban renewal project set up a target for new modern appearances instead of old historic ruins. As a result, many old industrial buildings of the city could only keep their memories into the city museum archives. After years’ urban development, a result is that China has received a bad reputation for destroying its historical roots as well as demolishing every old building.

Noticing that the rapid development of the creative industries in the western countries, gradually the urban planners realize that rather than absolute demolition it is possible to effectively repackage those old industrial buildings into the creative industries clusters, so as to rekindle the vitality of the original site and receive the same outcome as the former way of demolition. Soon, local governments and urban planners joining force with the land developers and the capital investors start another round of urban renewal through adopting the creative industries strategies.

2 Clustered Creative Industries and Real Estate Industries

Pasquinelli revisits David Harvey’s work of The Art of Rent (Harvey 2001), claiming that “all the immaterial economies have a material, parallel counterpart where the big money is exchanged†(2006:22). The mode of value generation in creative industries domain is in fact not limited to the exploitation of intellectual property, but also a more tendentious way of parasitic exploitation by another material objects. The discourse “collective symbolic capital†introduced by Harvey unveils the potential political economy of cultural interventions and the parasite exploiting the social creativity. The culture context provides the marks of distinction which be exploited further by capitalists to sell material goods. Pasquinelli states that the production of culture as social capital and real estate speculation is a couple of immaterial and material compound (ibid). Therefore, inspired by Pasquinelli’s argument, we try to decode the discourse of the creative industries into two parts: the culture and creativity as immaterial part; the clustered territory as material part.

2.1 The Culture and Creativity

Firstly, we draw on one of its subordinated elements: the culture and creativity. In his book The Rise of Creative Class, Richard Florida argued that “Creativity has come to be the most highly prized commodity in our economy†(2002:5). It also introduces a newly emerged social class as the “Creative Class†referring to those both being the source of “Creativity†in the rise of Creative Industries and contributing to the consumption for generating the economic growth in the cities; it seems a positive and productive circle. So, Florida argues that city’s economic prosperity and cultural attractiveness would increasingly depend on how the “Creative Class†is attracted and kept by the local strategies (ibid).

2.2 The Clustered Space

Another key element is concerning the cluster phenomenon. It is noted that the first interest to promote a cluster mode can be dated back to late 19th century. A British economist Alfred Marshall suggested the positive outcomes by clustering the related firms and industries to build a value chain (See in Flew 2010). Then in one decade later, another theorist Michael Porter put into effort to readdress the benefits of cluster as a business management mode (ibid).

Porter (1998) analyzed the cluster mode would bring about at least three competitive advantages to the involved industries, namely productivity gains, innovation opportunities, and new business formation. The first advantage refers to specialist inputs and skilled labor, enabling to promote the professional reputation and strengthen the collective power. The second one of innovation opportunities is focusing on the interaction with buyers and suppliers by emerging a present and compact value chain. The third one of new business formation is derived from better access to resource, such as venture capitalist, skilled workforce (See in Flew 2010:86-87). This notable cluster theory encourages the model of cluster spreading around. As noted earlier, other conceptual literatures have shed the light on spatial agglomeration and confirmed its capability to smooth the flexibility of information flows, interactive network and relation ties among the diverse but relevant industries (Scott et al 2001).

Taking account of above cluster characteristics, the urban policy makers in the stage of postindustrial cities began to combine the culture-led urban regeneration and the cluster mode (Schuster 2002). Practical cases like Hollywood and Silicon Valley demonstrate well the application of creative cluster theory. Except the initial startup in western countries, it also seems to find an even consistent role in countries like China where a collectivist ethos has long been cultivated by the state ideologies (Keane 2009a).

2.3 The Transfer: From Cultural Creative Cluster to Commercial Real Estate Industries

Summarized by Borg, Tuijl and Costa in their working report of creative industries in relation with Beijing urban development experience, there are at least two types of creative clusters: artists creative clusters and commercial creative clusters (2010:6). The artists creative clusters appear and grow ‘spontaneously’ by initiatives of artists who concentrate in a certain area to benefit from shared specialized field and inspiring artist environment. Differently, the commercial creative clusters are driven by real estate speculations and are much more planned, focusing on commercial spin-offs of art and culture. However, to name the representatives of the both, the artist creative cluster could refer to the original 798 art district; another type again could refer to 798 art district but in a later phase. In the same report, it records that through the transformation from artist creative cluster to commercial creative cluster, the most conspicuous difference is the growth of real estate price. Furthermore, the increasingly energetic commercial activities have also a profound effect in the form of rising rents. Some of the artists can’t afford the higher rents and have to move out of the area (ibid).

The familiar argument could be seen from Berghuis’ account of Dashanzi art district (2008). He argues that the most fundamental and essential development occurring here is indeed the real estate industry more than a contemporary art cluster Though, the place like Dashanzi district started as an experimental art basement of artists’ initiative, but it now ends up a trendy cultural cluster and commercial district whose biggest beneficiaries are property dealers. The loser could be the artists who contributed to the reborn of 798 art factory but eventually have to be driven off by the increasingly raised residential rent. In fact, the distinct culture context or creativity brand helps promoting the real estate speculation and generates a compound economy of creative industries and commercial industries (ibid).

3 Leading Actor or Supporting Actor

Following up the topic on the creative industries in relation to urban space production, this section scheduled to reflect forementioned literature thoughts into the performance of Ningbo creative industries in reality. The argument embedded is that the creative industries, for one hand, is a set of economic form, expected to generate economic growth and contribute to labor employment; on the other hand, it is also a tool, used to cover the underneath strategies for coalition between local government, real estate developer and commercial industries. We have chosen three observation sites for field work and systematically picked them up per differentiated phase categories. Phase one means the planning settled down and the project under construction; phase two refers to nearly finished project on a trial run; the phase three suggests the project formally on business.

3.1 Phase one: Hefeng Creative Square

The first observation spot is Hefeng Creative Square, located in the east bank of Yao River. Though only semi-finished architectural complex erects on site, the temporary enclosure wall presents impressive advertisements to attract potential companies and financial investment. Learned from the interview, the ambition of Hefeng is to establish a flagship industry in providing creative and innovative service to plenty manufactories in Ningbo area, not only compete with local service providers, but also those from Shanghai or others, even foreign countries. In regards with the decisive advantage for them to compete with other creative clusters, the interviewee emphasized the professional guide and training provided by cluster committee plus the golden location, the center of downtown Ningbo.

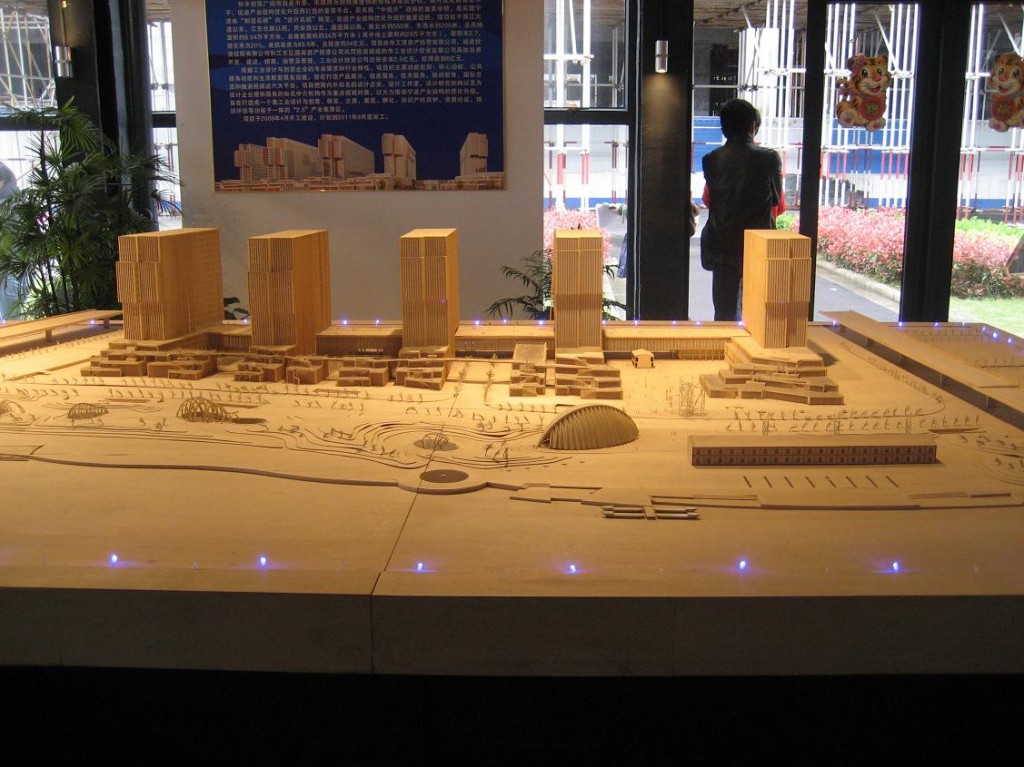

(Picture No.1: The Planning Map of Hefeng Creative Square)

The planning map demonstrates the square with a large plot in territory. Moreover, Hefeng creative square is not positioned as a simplex creative cluster, but integrated with commercial-oriented use like restaurants, hotel, shopping centre, and entertainment. The mode refers to the urban planner’s additional proposal that, besides the creative industries, they also conspire to develop real estate industries, commercial industries and tourism industries as well.

3.2 Phase two: Book City

The second spot is Book City. It is one of key culture and creative projects promoted by Ningbo Government. Situated oppositely to Ningbo Laowaitan, the site was once the flour factory of Ningbo. As same as Hefeng Creative Square, the structure of Book City is weaved as a matrix bonded culture and creative industries with commercial industries. The project of Book City is near to completion, and the key building which is the biggest one just celebrated its opening to public. To brand its culture meaning, Book City is titled as “City Reading Room on East Bank of Yong River †(CNNB 2010); for commercial promotion, it again advertise with “The First Culture, Tourism, and Commercial Plaza on Mouth of Three River†( Book City Billboard 2010, pic 2).

(Picture No.2: The Billboard Advertisement of Book City)

Since it is partially launched on business, we arrived at the site and did some anthropologist investigation. Next to Book City there is one normal-leveled residential community, so most retails around are accordingly small and simple ones including clothing shops, convenient stores and casual eating places. However, the propaganda of Book City promotes that the street beside will be the city’s future culture corridor. The most immediate effect observed on site is that some shops are closed for redecoration (maybe to upgrade); some change the business types. Moreover, we randomly interviewed some shop owners, some of them are optimistic about the benefits bought by Book City, for example, the existing restaurants; some complained the increased rent, such as low priced clothing shops.

In the case of Book City, the finding is to some extent the evidence to Keane’s argument that the Chinese experience of Creative Industries is mostly the Culture Industries (2009b). To decode the culture and creativity in a semiotic approach, these old buildings and old plants while transforming to the culture and creative cluster, it has become the visible imaginary symbols of the city culture and social experience.

3.3 Phase three: Fortune Creation Harbor

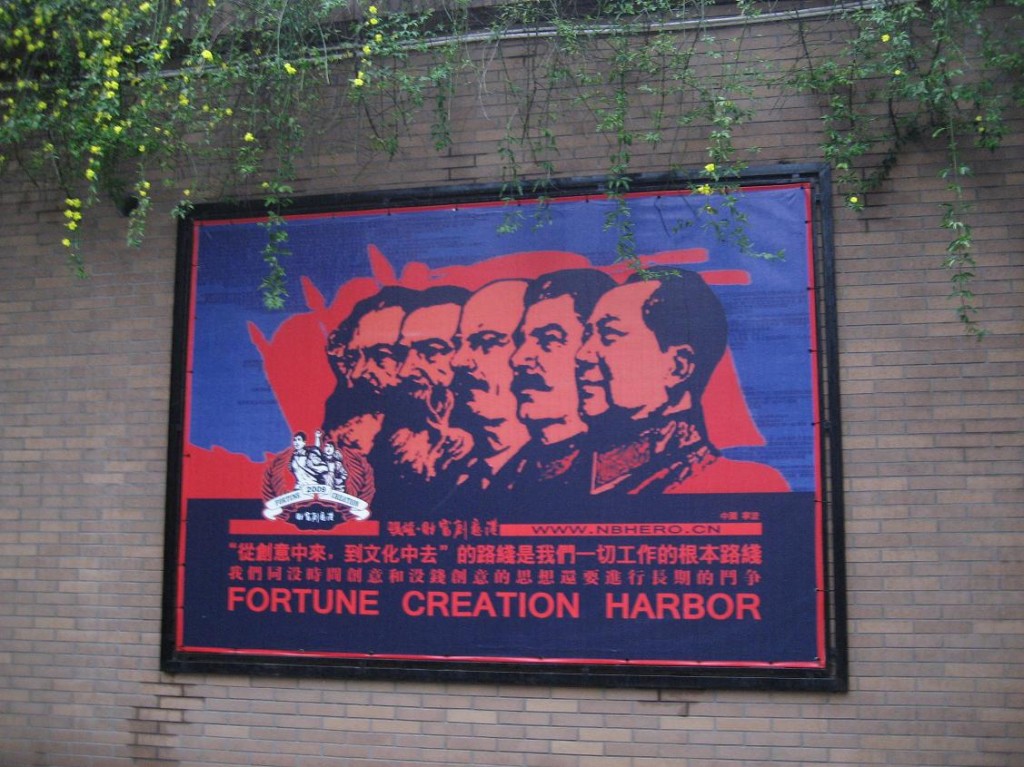

(Picture No.3: The Billboard Culture of Fortune Creation Harbor)

The last observation site is Fortune Creation Harbor situated in the North Bank Fortune Centre near to Ningbo Great Theater. At a first sight of the North Bank Fortune Centre, we noticed that though it covers huge territory with several high-end complexes, some offices seem empty and few pedestrians could be observed on site. When we get close to Fortune Creation Harbor, the situation is exactly the same, some companies removed out, some with no clue or little connection with creative industries.

Referencing to the initial design of Fortune Creation Harbor, it was once a key creative industries project promoted aggressively by Jiangbei government. The third picture attached above should have witnessed the prosperity once upon the time. However, two year later, the place shows more deserted and silent. It has failed to live up to the ambitions of their planners. We assume that this concerns much with the planner’s strategies for positioning the place. The basic mode is the same as of Hefeng Creative Square and Book City, to establish a comprehensive industries center, and the aim is to present a perfect package for attraction from real estate speculators and capital investor. Backed up by conspicuous state investments and by fast decision making, the areas have been transformed and neighborhoods have been revitalized, infrastructure has been upgraded. Unfortunately, a great leap forward can not guarantee a long term benefit.

Conclusion

In conclusion, to apply the concept of parasitic exploitation of symbolic capital (Pasquinelli 2006), the mode of development of creative clusters in local Ningbo seems a contradictory and conflicted. It confirms the situation of Ningbo’s creative industries that the culture and creative economy-oriented project is possibly exploited mostly by real estate speculators and leave little space for sustainable development of culture and creative reproduction.

Using the creative industries as overwrap, and then packaging the commercial oriented industries into creative economics, such a development mode of creative industries was copied by a lot of followers. As in Ningbo area, we’ve observed Loft8, Creation harbor and Creative 3rd plant established one and another designed in similar way. In a first sight, such creative industries may bring instant benefit as it successfully promotes the real estate speculation. However, the more in-depth and profound effect should be questioned and highlighted: how long could this mode of “fake†creative industries further go?

References

Berghuis, T, J(2008), ‘Constructing The Real (E)state of Chinese Contemporary Art: Reflections on 798, in 2004′ , Urban China 33 [Special Issue: ‘Creative China: Counter-Mapping Creative Industries’].

Borg, J, Tuijl, E and Costa, A, 2010, Designing the Dragon or does the Dragon Design? An Analysis of the Impact of the Creative Industry on the Process of Urban Development of Beijing, China, Retrieved May, 2010 from

http://www.dse.unive.it/fileadmin/templates/dse/wp/WP_2010/WP_DSE_borg_tuijl_costa_03_10.pdf

CNNC,2010. Special Website for Book City, Retrieved May, 2010 from

http://zt.cnnb.com.cn/system/2010/04/23/006500222.shtml

DCMS (2001), Creative Industries Mapping Document 2001 (2 ed.), London, UK: Department of Culture, Media and Sport, Retrieved May, 2010 from http://www.culture.gov.uk/reference_library/publications/4632.asp

Flew, T. 2009. ‘The cultural economy moment?’ Cultural Science. Retrieved May, 2010 from http://cultural-science.org/journal/index.php/culturalscience/article/view/23/79

Flew, T. 2010. ‘Toward a Cultural Economic Geography of Creative Industries and Urban Development: Introduction to the Special Issue on Creative Industries and Urban Development’, The Information Society, 26: 2, 85 – 91. Retrieved May, 2010 from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01972240903562704

Florida, R. 2003 The Rise of the Creative Class. New York: Basic Books

Harvey, D. 2001, ‘The Art of Rent: Globalization and the Commodification of Culture’, in Spaces of Capital: Towards a Critical Geography, New York: Routledge, 2001, pp. 394-411

Keane, M. 2009a ‘Creative industries in China: four perspectives on social transformation’, International Journal of Cultural Policy, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 431–443

Keane, M 2009b ‘Understanding the creative economy: a tale of two cities clusters’. Creative Industries Journal, 1(3). pp. 211-226.

Landry, C. 2000. The creative city: A toolkit for urban innovators. London: Earthscan

Lovink, G and Rossiter, N (eds) 2006, ‘MyCreativity: Convention on International Creative Industries Research’, MyCreativity Reader: Critique of Creative Industries, Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, pp. 241-247.

Pasquinelli, Matteo (2007) ‘ICW-Immaterial Civil War, Prototypes of conflict within cognitive capitalism’, in Geert Lovink and Ned Rossiter (eds) MyCreativity Reader: Critique of Creative Industries, Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, pp. 71-81.

Porter, M. 1998. ‘Clusters and the new economics of competition’. Harvard Business Review 76:77–91.

Rossiter, N. 2008, Counter-mapping Creative Industries in Beijing (Introduction), Urban China, No. 33, December 2008

Schuster, J 2002. ‘Sub-national cultural policy—Where the action is? Mapping state cultural policy in the United States’. International Journal of Cultural Policy 8:181–96

Scott, A,J (ed) 2001. ‘Global city-regions’. In Global city-regions: Trends, theory, policy, pp11–30. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scott, A. J 2008. Social economy of the metropolis: Cognitive-cultural capitalism and the global resurgence of cities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zukin,S 1989. Loft Living Culture and Capital in Urban Change. Rutgers University Press

Leave a Reply